What is a Worldview?

Ken

Funk

21 March 2001

The meaning of the term worldview (also world-view, world view, and

German Weltanschauung) seems self-evident: an intellectual

perspective on the world or universe. Indeed, the 1989 edition of the Oxford English Dictionary

defines world-view as a

"... contemplation of the world, [a] view of life

..." The OED defines Weltanschauung

(literally, a perception of the world) as "... [a]

particular philosophy of life; a concept of the world

held by an individual or a group ..."

In Types and Problems of

Philosophy, Hunter Mead defines Weltanschauung

as

[a]n all-inclusive world-view or outlook. A

somewhat poetic term to indicate either an articulated

system of philosophy or a more or less unconscious

attitude toward life and the world ...

In his

article on the philosopher Wilhelm Dilthy in The Encyclopedia of

Philosophy, H.P. Rickman writes

[t]here is in

mankind a persistent tendency to achieve a comprehensive

interpretation, a Weltanschauung, or philosophy,

in which a picture of reality is combined with a sense of

its meaning and value and with principles of action

...

In "The Question of a Weltanschauung" from his New Introductory Lectures in Psycho-Analysis,

Sigmund Freud describes Weltanschauung as

... an

intellectual construction which solves all the problems of our existence

uniformly on the basis of one overriding hypothesis, which, accordingly,

leaves no question unanswered and in which everything that interests us

finds its fixed place.

James W. Sire, in Discipleship of the

Mind, defines world view as

... a set of presuppositions ... which we

hold ... about the makeup of our world.

These definitions, though essentially in accord with one another and

seemingly not at all inconsistent with current usage, are somewhat

superficial.

Worldview in Context

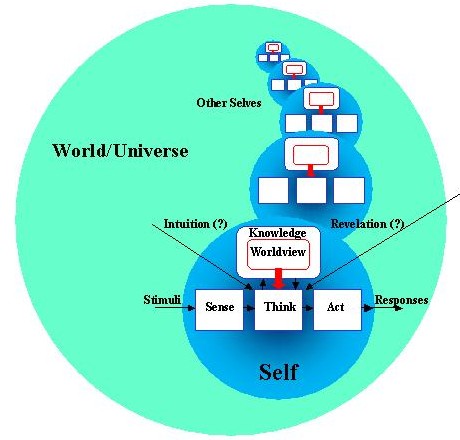

Figures 1 and 2 provide a

basis for a deeper understanding of worldview. The sensing,

thinking, knowing, acting self exists in the milieu of a world

(more accurately, a universe) of matter, energy,

information and other sensing, thinking, knowing, acting selves (Figure

1). At the heart of one's knowledge is one's

worldview or Weltanschauung.

Figure 1. The self and its worldview in the context of the

world.

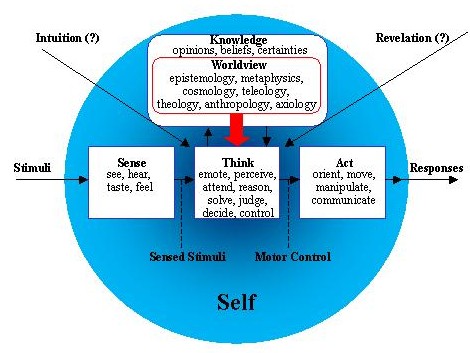

To sense is to see, hear, taste, and feel

stimuli from the world and from the self (Figure 2). To act is to

orient sensory organs (including eyes and ears), to move

body parts, to manipulate external objects, and to

communicate by speaking, writing, and other actions.

Although we humans are not unique in our ability to sense

and to act on our environment, it is in us, so far as we

know, that thought as the basis for action is most highly

developed.

Thought is a process, a sequence of mental states or

events, in which sensed stimuli and existing knowledge

are transformed to new or modified knowledge, some

instances of which are intents that trigger motor control

signals that command our muscles to action. While some

actions are merely the result of sensorimotor reflexes,

responses to emotions like fear or anger, or automatized

patterns developed through habit, we at least like to

believe that most of our actions are more reflective,

being based on "higher" forms of thought.

For example, there is in most sensory experience an

element of perception, in which sensed stimuli are first

recognized and interpreted in light of existing knowledge

(learned patterns) before they are committed to action.

And to bring thought to bear on some stimuli or knowledge

rather than others requires a focusing of attention, an

allocation of limited mental resources to some mental

activities and away from others. But it is in our reason

-- and specialized forms of reason like problem solving,

judging, and deciding -- that we take the most pride.

Reasoning is focused, goal-directed thought that

starts from perceptions and existing knowledge and works

toward new and valued knowledge. Reasoning therefore begins with

knowledge and ends with knowledge, the opinions, beliefs, and certainties that one holds. By

inductive reasoning (which is idealized in empirical

science), one works from perceptions and other particular

knowledge to more general knowledge. By deduction

(exemplified by mathematical logic) further

generalizations and, more practically, particular

knowledge, is produced. Over a lifetime, reason builds up

not only particular opinions and beliefs, but also a body

of more and more basic, general, and fundamental

knowledge on which the particular beliefs, and the

intents for external acts, are based. This core of

fundamental knowledge, the worldview,

is not only the basis for the deductive reasoning that

ultimately leads to action, but also is the foundation

for all reasoning, providing the standards of value to

establish the cognitive goals towards which reason works and to

select the rules by which reason operates. The large red

arrows in Figures 1 and 2 symbolize the absolutely

crucial role that the worldview plays in one's behavior.

Figure 2. The worldview in the context of the self.

To put this more concisely, and consistently with the

definitions considered above,

A worldview is the set of beliefs about fundamental aspects

of Reality that ground and influence all one's perceiving, thinking, knowing, and

doing.

One's worldview is also

referred to as one's philosophy, philosophy of life, mindset, outlook on

life, formula for life, ideology, faith, or even religion.

The elements of one's worldview, the beliefs about

certain aspects of Reality, are one's

- epistemology: beliefs about the

nature and sources of knowledge;

- metaphysics: beliefs about the

ultimate nature of Reality;

- cosmology: beliefs about the

origins and nature of the universe, life, and

especially Man;

- teleology: beliefs about the

meaning and purpose of the universe, its inanimate elements, and

its inhabitants;

- theology: beliefs about the

existence and nature of God;

- anthropology: beliefs about the

nature and purpose of Man in general and, oneself in particular;

- axiology: beliefs about the nature of value,

what is good and bad, what is right and wrong.

The following elaboration of these elements and their implications to

thought and action is based on Hunter Mead's Types and Problems of

Philosophy, which I highly recommend for further study. For each worldview element I

pose for you some

important questions whose answers constitute your corresponding beliefs. I

suggest a few possible answers you could give to these questions. Then I present

some of the implications those beliefs could have to your thought,

other beliefs, and action.

But first I must acknowledge some

assumptions that underlie or constrain what I say.

First, your worldview may not be explicit. In fact few

people take the time to thoroughly think out, much less

articulate, their worldview; nevertheless your worldview

is implicit in and can be at least partially inferred from your behavior. Second, the elements of

your worldview are highly

interrelated; it is almost impossible to speak of one

element independently of the others. Third, the questions I pose to you are not

comprehensive: there are many more, related questions that could be

asked. Fourth, the example answers I

give to the questions -- that is, worldview beliefs -- are not

comprehensive: many

other perspectives are possible and you may not find your answers among

those that I suggest. But, I hope, they illustrate the points.

Fifth, my assertion that your worldview influences your action is based on the assumption

that thought is the basis for action and knowledge is the

basis for thought. Of course, as I wrote above, some actions are reflexive

or automatic in nature: conscious thought, much less

knowledge and, especially, worldview, probably have

little direct influence on them. Nevertheless, even

highly automatized or impulsive actions often follow patterns

of behavior that originated in considered acts. Finally,

my exposition of worldview is based on my own worldview and the

questions that I choose to pose to you, the possible answers that I give as

examples, and even the way I present those example answers are colored

by my worldview.

Epistemology

Your epistemology is what you believe about

knowledge and knowing: their nature, basis, and validation.

Epistemological Beliefs

What is knowledge? You may believe

that knowledge is simply information. Perhaps you consider it merely a state of the

brain, the result

of the actions of neural mechanisms. Or possibly it is something deeper

than information or mechanism: the state of a not

wholly material mind that exists for the time being on a

fleshy substrate and that will persist even after the substrate has long since died and decayed. Maybe you believe that your

knowledge is a localized manifestation of the

contents of a Cosmic Mind.

What is knowing? You might believe that knowing is a

passive response to sensory evidence or an act of trust or commitment in the absence of any

external guarantee.

What is the basis for knowledge? You may hold that the only valid basis for knowledge is empirical

evidence derived from sensory experience, or that reason is the

supreme authority for knowledge. Perhaps you consider authority, in the form of books or people,

as

the most reliable source of knowledge. Perhaps, to you,

intuition -- a direct perception of the world,

independent of sense or reason -- provides the best

evidence for knowledge (see Figure 2), or maybe

revelation -- direct apprehension of truths coming from

outside of nature -- is the supreme source of knowledge. More likely

than any of the above opinions, you affirm that no single source of evidence for

knowledge is sufficient, but instead you ascribe certain relative weights

to authority, empirical

evidence, reason, intuition, and revelation.

What is the difference between knowledge and

faith? You may see a profound distinction between knowledge

and faith, the former being

validated certainty, the latter fanciful, ungrounded hope. On the other

hand, you may view knowledge as a continuum based on your level of confidence in a proposition, with

faith, opinion, and certainty being merely points

along that continuum.

Is certainty possible? You may think that it

is possible to have complete certainty about some knowledge or that it

is presumptuous -- even dangerous

-- to claim certainty about anything of consequence.

Epistemological Implications

Your epistemology, what you believe about knowledge, affects what you

accept as

valid evidence and therefore what you are willing to

believe about particulars. It affects the relative

significance you ascribe to authority, empirical

evidence, reason, intuition, and revelation. It affects

how certain you can be about any knowledge and therefore

what risks you will take in acting on that knowledge.

If knowledge is

merely brain state, then true knowledge in the sense of

its correspondence to the actual state of the world is

suspect. Your beliefs, and therefore your acts, are at the mercy of your

neural machinery and are valid and valuable only to the

extent that those mechanisms correspond to reality;

confidence and certainty must be suspect to you. At the

opposite extreme, if knowledge is an extension of a Cosmic

Mind, then you may feel that you can claim access to real truth, perhaps directly

through revelation, and that your actions can be grounded in

fundamental reality.

If you hold reason to be the paramount basis for

knowledge, then you must discount any hypothesis that cannot be validated

rationally and you cannot use such a hypothesis as a reliable

basis for action. If you believe sensory evidence to be

the test of truth, then knowledge must be verified

empirically before it can be the grounds for your thoughts or acts. If you rely on intuition or revelation,

"lower" forms of evidence are discounted. If

you depend on authority to validate knowledge, you will

be reticent to believe, think, or act without the

blessing of some external source of authority.

If you believe certainty is possible, you can have

complete confidence in the validity of thoughts and

actions. You will feel justified in taking extreme

measures to secure valued ends, even at the risk of

being branded a fanatic. On the other hand, if you doubt

the possibility of absolute certainty, you are more

likely to assume an attitude of intellectual humility and

be more prone to conservatism and moderation in your

behavior.

Metaphysics

Your metaphysics are the beliefs you hold about the

ultimate nature of Reality.

Metaphysical Beliefs

What is the ultimate nature of Reality?

If you are a philosophical naturalist (sometimes called a

materialist), you believe that the universe consists

solely of matter, energy, and information and that there

is nothing outside that material universe. The universe

is mechanistic and uncaring and there is no Mind or God

or Spirit that created it, guides it, or even considers

it. On the other hand, if you are a philosophical

idealist, you believe that Reality is ultimately noumenal

(of the Mind) or spiritual in nature. There is a supernatural Something outside

and above

nature that created it, and perhaps even now has a part in

guiding it. There is a moral order to the universe: good

is not only desirable but possible, achievable, perhaps even inevitable.

What is Truth? There are three major

theories with respect to truth. If you subscribe to the

correspondance theory of truth, you believe that truth

corresponds to what really is, that there is a direct

relationship between true knowledge in your mind or brain

and what actually exists outside yourself. If you believe

that such a strict definition of truth is unrealistic,

you may believe that truth is merely that knowledge which

is internally consistent. That is the consistency theory

of truth, whose archetype is mathematical logic, where

consistency is a necessary condition for any proposition

to be considered valid. If you are a pragmatist, you hold to the pragmatic

theory of truth: truth is what works. Whether or not

knowledge corresponds to external reality and whether or

not it is consistent with other knowledge is immaterial.

What counts is that what you believe to be true leads to valued ends. If it works

for you, it is true for you, though it might not be true for someone else.

What is the ultimate test for truth?

This question and its possible answers parallel the

epistemological question concerning valid bases for

knowledge. You may hold that some authority -- some book

or person or organization -- holds the keys to truth:

whatever he/she/it says is true. As an empiricist, you

may hold that truth is discovered only by empirical inquiry. If you are

a rationalist you would say that truth is found through valid

inductive and deductive reasoning. On the other hand, you

may believe that you know the truth directly through

intuition or even revelation.

Metaphysical Implications

If you are a philosophical naturalist (equivalently, a materialist) and believe that nothing exists

outside of the physical universe, then you can believe in

no spiritual realm, no God. There can be no absolute,

externally valid standards of value and morality; any

standards are simply (collective) choices or norms,

simple artifacts of human biology, human inventions with

no broader significance. In the end, the individual

person is free to choose his or her morality and act as

he or she sees fit, without fear of violating any absolute, objective, universal rules. Life itself being

material, there is no afterlife and no reward or

punishment for "good" or "bad"

behavior. There are no absolute personal

responsibilities, no obligations, and since there is no

One or Thing to reward or punish "good" or

"bad" behavior, in the end there are no significant consequences of it.

On the other hand, if you believe that Reality is

ultimately spiritual in nature, there is room for a God

or gods and just possibly an absolute and eternal moral order to which

you may be responsible. You may have an accountability

for your acts that goes beyond just yourself, your

family, your friends, your community, or your government.

You may have a moral obligation to believe, think, and

act in conformance with that supernatural reality and you

will probably try to do so, at least part of the time.

With regard to truth, if you subscribe to the

correspondence theory of truth, then you are more likely

to seek truth, by thought and act, outside yourself. If

you hold to the consistency theory of truth you may be

content to rely on reason as a primary means for

discovering truth. If you are a pure pragmatist, you will discount the

notion of absolute truth as irrelevant and will search

for truth only as far as is needed to realize practical ends, whatever

you determine them to be.

Cosmology

Your cosmology consists of your beliefs about the origin of

the universe, of life, and particularly, of Man.

Cosmological Beliefs

What is the origin of the universe?

One possible answer to this question is chance:

the universe as it exists now is simply the mechanical

response of matter and energy to random events and the laws of physics over

a very long time. Standing in direct opposition to this is

the notion that the universe is the result of the acts of

a supernatural Creator that formed the universe ex

nihilo (out of nothing).

What is the origin of life? What is the origin

of Man? Here again, you may believe that life,

and even the human race, is the result of chance, random

events, and natural selection. At the opposite end of the

cosmological spectrum is the belief that Something

outside of nature instantaneously created life pretty

much as we see it today. Some hold an intermediate

position, that of a gradual rise of plant, animal, and

even human life from non-living matter, not by mere

chance and natural selection, but through guidance by a

divine shepherd or helmsman, towards a desired end,

according to a plan or purpose.

Cosmological Implications

If you believe that things came to be primarily by

chance, then the universe, the laws of physics, life in

general, and even human life have no universal significance. This in turn implies that human thought and

action themselves have limited significance: in the Big Picture, one

thought or act is equivalent to any other.

On the other hand, if the universe was created by a

Designer, presumably that Designer had a plan or purpose

and what you are or do can, and perhaps therefore should,

be consistent with that plan.

Teleology

And that is the substance of your teleology, your beliefs about purpose.

Teleological Beliefs

Does the universe have a purpose?

Obviously, one possible answer is No. You may

believe that the universe has no goal or desired end

other than what its inhabitants choose to establish and

pursue. The alternative is to believe that there is some

purpose: some purposive Agent has either created the

universe according to a plan or has "adopted"

the universe, but in either case wishes for it some

process or end state.

If the universe has a purpose, whose purpose

is it? If you believe that the universe has no

purpose, then of course this question is meaningless. On

the contrary, given a purpose, there must be a purposive

Agent. You probably believe that this is God or a god or

gods, but perhaps you consider its personification only

anthropomorphism, that Agent transcending personhood.

What is the purpose of the universe?

Here there are many possible answers, the simplest one

being that this purpose is unknown, even

unknowable. Perhaps you believe that the purpose of the

universe is an ever-increasing complexity and

interdependence of its elements. Maybe it is a growing

consciousness of its inhabitants and ultimately a

self-consciousness on the part of the universe itself.

You may believe that there is no more purpose to the

universe than simply the happiness of its conscious occupants. If you believe in God (see below), knowledge

of or communion with God by its conscious inhabitants may

be the Grand Purpose.

Teleological Implications

If the universe has no purpose, then we have no

obligation to fulfill other than what we, perhaps collectively,

choose. There is no accountability to Something higher

than ourselves and no meaning to life other than what we

choose. In the end, our acts cannot be judged according

to a universal purpose, so there is no real fear of "missing

the mark." Our acts are neither justified nor not

justified by conformance or lack of conformance to a Plan. There can be no

direct link between is and ought; in

fact, ought may be a meaningless term.

But if there is a Plan or Purpose to the universe we

may have an obligation to think and act consistently with it,

and therefore life may have meaning in its context. There

can be a link between is and ought and

this may (or at least should) make us try to act as in certain ways. Of

course, obligation may not be the right term to use in

regard to this Purpose: if free will is an illusion, we

may have no choice but to behave in a manner consistently

with the Purpose, being mere automata whose actions were

pre-programmed before time.

Theology

Your theology is comprised of your beliefs about

God.

Theological Beliefs

Is there a God? If you are a theist you say yes,

if an atheist no, and if an agnostic you say maybe.

Theists differ as to the number of gods: traditional

western belief (that is, post-classical) is monotheistic,

but many people believe in multiple

gods.

What is God's nature? Assuming that

you believe in a God or gods, there are many possible

beliefs about His/Her/Its/Their nature. For the sake of

simplicity, I will give monotheistic, masculine examples,

but they can be generalized. Most likely you believe that

God exists outside of and above nature. You may believe

that He is a localized Person or that God transcends

personhood. He may be benevolent or tyrannical, loving or

indifferent, omnipotent or limited in power, omniscient

or only partly knowledgeable of what is going on in the universe.

What is the relationship of God to the

material universe? He may be the creator or just

a chance companion to it. If He is the Creator, he may

have made it and left, being now sort of an absentee

landlord (the position of deism), or He may still be

interested in and intimately involved in perhaps all of

its doings. If you are a pantheist, you probably hold

that God and the universe are One.

What is the relationship of God to Man?

God may be a loving parent or a childish tyrant. He may

be lawgiver, policeman, judge, and executioner or a

caring but just disciplinarian. You may believe that God

is indifferent to the activities of us humans or that He

desires an intimate relationship with each individual

person. Perhaps God speaks to us or perhaps he has left

us to work things out on our own.

Theological Implications

If there is no God, then you must look elsewhere for a

source of and purpose for the universe. With regard to

your behavior, there is no One to be accountable to, no

One to obey, no One to talk to, no One to love, and no

One to look to for help in time of need -- nor are any of these

necessary. But if you

believe in God, then perhaps you believe that you do have

an obligation, that you ought to think and act so as to

please Him, that you have the privilege to communicate

with Him, and that you ought to be in proper

relationship with Him.

Anthropology

The term anthropology usually refers to the

study of human culture and human artifacts, but in the

context of worldview, I take it to mean your beliefs

about Man. I do not wish to be sexist, but to avoid

cumbersome prose as much as possible, by Man I

mean all humans, of both genders and all ages.

Anthropological Beliefs

What is Man? Man may be merely a

cosmic accident or just one step in the directionless

chain of evolution. Maybe you believe that

though Man is an evolutionary step, that step is nevertheless a

very important one on the path to some valued end. If

you are a theist you may see Man as the gem of God's

creation or even a creature created in His own image.

At the extreme, you may consider Man a part of God or

even a god himself.

What is Man's place in the universe?

Man may be an infinitesimally, insignificant part of the

universe or a key step in the progress of evolution

towards new and better beings. He may be merely a part of

earth's global ecosystem or a steward responsible for the

well-being of the lower organisms and the inanimate

elements. Perhaps you would go so far as to say that

Man's unique place in the universe is as a moral agent,

to think and act in such a way as to realize the good.

Does Man have free will? Perhaps not:

perhaps we are mechanisms, slaves to our instincts and/or conditions and events beyond our control. Perhaps we are

puppets of God, acting out a script that we had no part

in writing. But maybe you believe that we do have the ability to think and act with at least partial freedom. Though

there may be constraints, imposed by the laws of physics

and biology or the guidance of God, we do have choices, for which we may be responsible.

What ought Man to do? Maybe you

believe that you have no obligation to anyone or anything

beyond yourself (if you so choose). Or maybe you do have

a responsibility for the well-being of the universe in

general and Man in particular. Perhaps you have a

responsibility to believe in, love, obey, even enter into

communion with God.

Is Man basically good or evil?

Perhaps beliefs about good and evil belong more properly

in your axiology (see below), but this question is

fundamental to your view of Man. Although western

thought, grounded in principles of Christianity, held

fallen Man to be fundamentally sinful and continually striving

against his evil nature, and although that belief is

still held by some today, it is more likely that you

believe that people are basically good and only

wanting the environment and the opportunity to express

that goodness. Maybe even more common is the belief that

Man is basically neither good nor evil, but morally

neutral from birth, and whether one follows a path of

good or evil depends on external influences and strength

of will.

Anthropological Implications

If we are mere mechanistic

elements of the universe, then we are free to think and

act on impulse and we and our behavior have no special

significance or value. If we are stewards of the creation

of God, then we have a responsibility to take care of our part of the

universe. If we are created in God's image, then we have

great intrinsic value and we should see to our own and,

especially, to others' well-being. If we are moral

agents, then we have an obligation to know what is good

and to do well what is right. If we are basically good,

then that obligation should be a light one and we merely

need to be sensitive to and to follow our own natural

inclinations -- and help others do the same. If we are

born morally neutral, then things are only a little more

difficult: moral goodness must be cultivated and rewarded

and evil must be discouraged and, fortunately, there is

nothing working in us to resist such moral training. But

if Man is basically wicked, then we should resist certain

natural inclinations to evil, and seeing that evil is so

intrinsic to our nature and such resistance is ultimately

futile, we must look to Someone or Something higher than

ourselves for forgiveness, redemption, and moral strength

to behave as we ought.

Axiology

The term axiology comes from the Greek axios

or worth. In philosophy, axiology is that field that concerns itself with the subject of value and all

pro and con assertions. In the context of worldview, your axiology

consists of your beliefs about the nature of value and

what is valuable: what is good and what is bad, what is

right and what is wrong. Virtually all elements of your worldview, from

your epistemology to your anthropology,

are intimately related to your axiology and it is your beliefs about the value of things that are the proximate

cause for most of your behavior.

Axiological Beliefs

What is value? Maybe you define value

in terms of worth, but if so you run into the problem of circularity,

for worth is usually defined in terms of value. Perhaps you believe that value is merely a personal preference for things. You may believe that

value is the interest someone has in a thing, the degree

to which something is the fulfillment of some desire, or

even the true object of someone's desire. Bucking the present

trend of relativistic thinking, you might consider value

to be a property of the elements of the universe as

concrete (though not as obvious) as shape and size. All such definitions are problematic and it may

be simpler (and perhaps more correct) to believe that

value is a primitive, indefinable term that every

thinking person understands without explanation.

What kinds of value are there? You

may think that value is value. But more likely, you

acknowledge that there are several kinds of value:

non-moral values (economic value, aesthetic value, simple

goodness), and moral value (the extent to

which a thought or act is morally right or wrong).

Is value objective or relative? You

may believe that value is objective, that it is inherent

in the object of consideration and independent of

anyone's assessment of it. Value is then "built

into" the universe, a fundamental, metaphysical

reality. Or perhaps you believe that value is subjective,

that it exists only in the mind of the subject (e.g.,

you) and therefore varies from subject to subject. If

so, you must believe that an object has no value

independent of a subject that assesses it.

Is value absolute or relative? You

may believe that value is absolute, that there is an

absolute, eternal, and universal standard of value which

applies to all people and any other

moral agents for all time. Perhaps, on the contrary, you

believe that value is relative to a time, a place, a culture or an individual: there are no standards

of value that apply under all circumstances.

Perhaps the last two questions seem to be the same

and, indeed, they are very closely related. But they are

different, as the following table illustrates.

| |

and value is objective ... |

and value is subjective ... |

| If value is absolute ... |

then value is inherent in the

object and is eternally and universally constant. |

then there is one Subject whose

standards are universally and eternally valid. |

| If value is relative ... |

then an object's inherent value

may change over time or space (i.e., value is a

dynamic property of the object). |

then value is inherent in the

subject but is relative to the time and place in

which the subject assesses it. |

What is the source of value? This

follows closely from, but is not identical with either of, the

previous two questions. The value of a thing or act may

be imposed by the self or it may be decided by a society

or culture. Perhaps you believe that value comes from the

very nature of the universe. Some believe that value is

defined by God or the gods.

What is the highest good? Although

there is often surprising agreement about whether a thing

is good or bad, one aspect that distinguishes one individual's

axiology from another's is the extent of goodness

ascribed to a thing, that is, how good or how

bad it is. Each of us has a hierarchy of value,

whose apex is the highest good, our summum bonum,

perhaps the single most distinguishing feature of one's

worldview. To the hedonist, the highest good is pleasure

or happiness; to the aesthete it is beauty; to the

philosopher, truth; to the scholar it may be knowledge;

to the naturalist it may be nature in its undisturbed

order and splendor. If you are a secular humanist you

likely consider humans and their well-being the highest

good, a closely-related summum bonum being

self-realization: the full realization of one's

capacities or potentialities. Technological Man ascribes

great value, perhaps the greatest, to power, speed,

efficiency, productivity, or information. To the

religious the summum bonum may be God or perhaps

it is intimate knowledge of, or communion, or mystical

union with God.

What is right? What is right or wrong

follows from what is good or bad, and besides being at

the peak of one's hierarchy of value, one's summum

bonum is something to which all acts could and

indeed should potentially lead. The simple answer to the

question posed by this paragraph is that what leads to

the good is right and what leads away from it, to the

bad, is wrong. Depending on your beliefs about

what is good and, especially, about what the summum

bonum is, you may believe that whatever brings pleasure

or happiness is right and what leads to pain is wrong.

Acts that create beauty or lead to knowledge of truth are

held to be right by many. Other candidates for right

behavior are acts that preserve the natural order,

behaviors that help one realize his innate potentialities

and capacities, or courses of action that realize speed,

efficiency, power, productivity, or the possession of

information. To those that hold God or the things of God

as the highest good, what is right, indeed one's moral

obligation, is to love and obey God and perhaps to seek His

Kingdom.

Axiological Implications

It is impossible to overstate the importance of your axiology in determining

your behavior. It is the

foundation for all of your conscious judgments and decisions and therefore the basis for all

purposive thought and action. Although some acts are

reflexive or instinctive and cannot therefore be ascribed

to conscious reference to your beliefs about value, any

action based on even the most cursory reflection has its

foundation in your standards of what is good or bad,

right or wrong.

Regarding your beliefs about the nature of value

itself, if you believe that value is relative and

subjective then you need not worry that your standards of

value are more or less valid than anyone else's; there

can be no universal standard against which to judge your

thoughts and acts. If value is relative and subjective you have no moral obligation to act in

a certain way: you are free to choose and abide by (or

ignore) any standards you create yourself or adopt from

society; you need feel no guilt for being "bad" if you

have been true to your standards. On the other hand, if you believe

value objective and absolute, you do have moral

obligations; there is a right set of standards to judge

against; and you should think and act according to those

standards.

Regarding your beliefs about the value of things, if

your summum bonum is pleasure, then you may, and

indeed should, act in such a way as to yield the greatest

possible pleasure and avoid pain, your own and perhaps

others'. If your summum bonum is truth, you may

seek knowledge, information, or even just data, and trust

to authority, sensory evidence, and/or your own rational

capacity to judge what is true. If your highest good is

beauty, you may seek to create it yourself or find it in

nature or in the works of others. If it is human

well-being (however you define it), you may strive to

realize it directly through your own behavior or

indirectly by encouraging or exhorting others. If it is

self-realization, you may try to identify your own (and

others') personal potentialities and cultivate them to

their fullest expression. If you believe that some

combination of speed, power, efficiency, and productivity

is the highest good, then you may seek it through your

own work as a scientist, engineer, or inventor or by

acquiring and using the technologies developed by others.

If your summum bonum is God, you may seek Him

and His Kingdom and try to think and act in such a way as

to please Him.

Conclusions

In summary, your worldview is the set of beliefs about fundamental aspects

of Reality that ground and influence all your perceiving, thinking, knowing, and

doing. Your worldview consists of your epistemology, your

metaphysics, your cosmology, your teleology, your

theology, your anthropology, and your axiology. Each of

these subsets of your worldview (each of these views) is highly interrelated with and affects virtually all of

the others.

I claim that you have a worldview and that your

worldview (especially your axiology) is the

basis for and therefore fundamental to what you believe

about the particulars of reality and what you think and

do. If you deny that you have a worldview, then you are

naive, willfully ignorant, or simply misled; you cannot

argue your case to the end, for to do so you must invoke

more and more fundamental beliefs, leading you ultimately

to what I have defined as your worldview. If you deny

that your worldview fundamentally affects what you think

and do, then you must acknowledge that your behavior is

impulsive, reflexive, or emotional at best; ignorant or

irrational at worst.

Assuming that a worldview can be incorrect or at least

inappropriate, if your worldview is erroneous, then your

behavior is misguided, even wrong. If you fail to

examine, articulate, and refine your worldview, then your

worldview may in fact be wrong, with the above consequences, and

you will always be ill-prepared to substantiate your

beliefs and justify your acts, for you will have only

proximate opinions and direct sensory evidence as

justification.

If you fail to be conscious of your worldview and fail

to appeal to it as a basis for your thoughts and acts,

you will be at the mercy of your emotions, your impulses,

and your reflexes (not that such responsive behavior is

always bad); you will be inclined to "follow the

crowd" and conform to social and cultural norms and

patterns of thought and behavior regardless of their

merit.

If you are unwilling to acknowledge and articulate

your worldview, to make known your fundamental opinions,

and to bring to the front of discourse your basic

beliefs, you are being intellectually evasive at best or

dishonest at worst. Those around you must always be in

the dark concerning your underlying beliefs and motives.

They will be forced to guess (perhaps wrongly) the true

meaning of what you say and the purpose of what you do.

If you consider a worldview a private matter and take

steps to prevent the open discussion of worldviews, you

are in fact imposing your worldview on others; by doing

so you would deny individuals the opportunity to bring

their own worldviews fully to bear on matters of common

concern and the opportunity to examine their worldviews

in the light of others'; you would effectively restrict

public discourse to trivialities and ungrounded

assertions.

On the other hand, if you use a position of power or

authority to impose your worldview on others or somehow

force or coerce others into adopting elements of your own

worldview, you are denying them the opportunity to seek

out their own answers to the important questions posed

above; you may be personally responsible for condemning

them to life with an erroneous worldview; you may be

denying truth and goodness a chance to manifest

themselves in those who you are manipulating; and anyway, in the

end, if and when your power over them wanes, they may

come to reject, even abhor, the beliefs you have imposed upon them.

Your worldview -- anyone's worldview -- is too

important to ignore. If there is such a thing as

obligation, we as knowing, thinking beings have an

obligation to examine, articulate, refine, communicate,

and consciously and consistently apply our worldviews. To

fail to do so is to be something less than human.

Socrates, during his trial for being impious to the Greek gods

and corrupting the youth of Athens by his teachings, said

"... the unexamined life is not worth living

..." (Plato, Apology). He was right, and

without complaint he accepted the sentence of death to

prove it. There can be no stronger testimony to the

validity of these assertions than that.

What's New

Following, listed most recent first, are significant

changes made to this page since its creation.

21 Mar 01

- revised short definition of worldview: A worldview is the set of beliefs about fundamental aspects

of Reality that ground and influence all one's perceiving, thinking, knowing, and

doing.

1 Jul 00

- second draft

- smaller figures

23 Jun 00

|