\(\newcommand{\hforward}{\stackrel{\rightarrow}{h}}\) \(\newcommand{\hbackward}{\stackrel{\leftarrow}{h}}\)

In the previous Exploration, we discussed word embeddings, which maps discrete words to continuous vectors, enabling deep learning to process language. However, language is far more complex than a bag of words; instead, a sentence is a linear sequential order of words, and word order does matter (e.g., “John bit a dog” is different from “A dog bit John”). So deep learning should also be able to process sequences of words. So here we introduce deep learning models for sequential objects.

The classical method of deep learning for sequences is recurrent neural nets (RNNs) which was a popular topic in the 1980s (along with CNNs for vision).

Generally speaking, at each step, an RNN transforms input to an output with the help of a memory state, and modifies the memory state to help it to better perform future processing. The memory state is therefore the key part of an RNN, enabling it to handle sequential data, and is usually implemented as a hidden vector that summarizes the previous input-output pairs.

Now let’s look at how to use RNN to do machine translation, one of the most important tasks in natural language processing and one of the holy grails of AI.

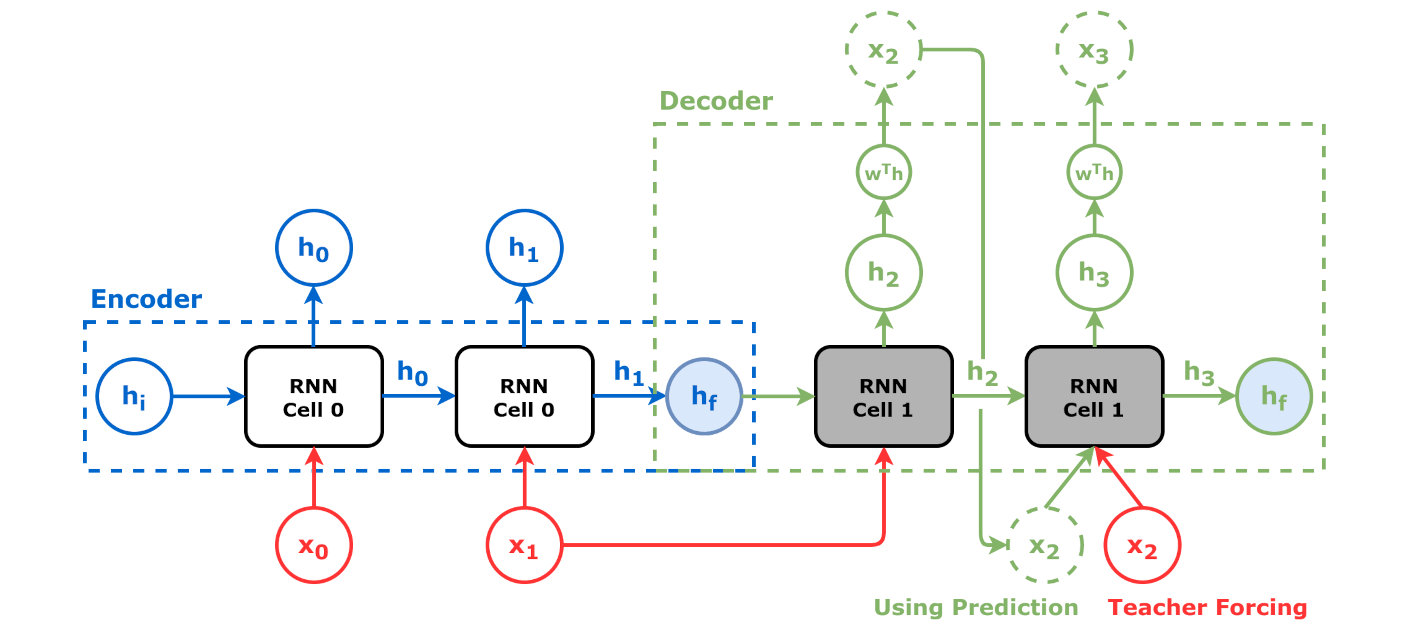

We use two RNNs, one for understanding (or “encoding”) the input sentence (say, in Chinese) called the “encoder” and one for generating (or “decoding”) the output sentence (say, in English) called the “decoder”. Both RNNs work word-by-word. After processing each input word, the encoder gives its final hidden state (which summarizes the whole input sentence) to the decoder as its “initial state”. The decoder then generates the first output word based on that initial state, and then feeds that word back into the decoder to generate the next word. The reason why the decoder always needs to take the previously generated word as input is because the hidden state is lossy compression of the history, i.e., not a perfect one, so having the previous word makes sure the output is fluent.

However, if you think about it a bit more, you realize the vanilla encoder-decoder architecture is problematic. The RNN has an imperfect memory, and naturally remembers recent things much better than remote history. Therefore, the encoder final state is mostly about the last few words of the input sentence; but it is used to initiate the decoder and is most impactful on the first few words of the output sentence! Unless the word order is completely the opposite between the input and output languages (which is unlikely because most of the worlds’ languages are either subject-verb-object like English or subject-object-verb like Japanese), this is whole paradigm is completely wrong!

To alleviate this problem, some researchers thought, if the input and output languages have similar word order (like English and French), why don’t we run the encoder backwards on the input sentence? This way, the encoder final state is most sensitive about the first few input words, which is consistent with the decoder. Well, this method does improve upon the vanilla one, but is still so wrong: what if the input and output languages have very different but not oppposite word order, like English to Japanese?

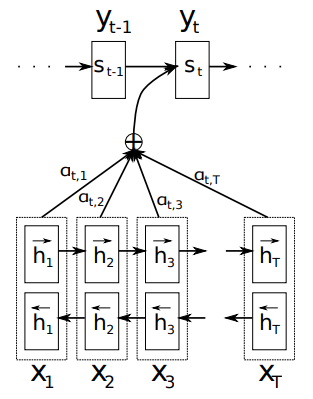

Luckily, in 2014, Yoshua Bengio’s group (recall that Bengio later won the Turing Award with Hinton and LeCun) found a nice solution using the concept of “attention” (which also paved way for Transformer). This solution has the following key points:

Here is a more detailed illustration of bidirectional encoder and attention between decoder and encoder:

This is a major breakthrough in deep learning and natural language processing, which paved the way to Transformer, the dominating architecture that led to the LLM revolution today.

Only three years after the attention work, Google published a groundbreaking paper, “Attention is all you need” (2017). The idea is revolutionary: completely get rid of RNNs and only use attention to model sequential data!

Why is RNN not the ultimate solution?

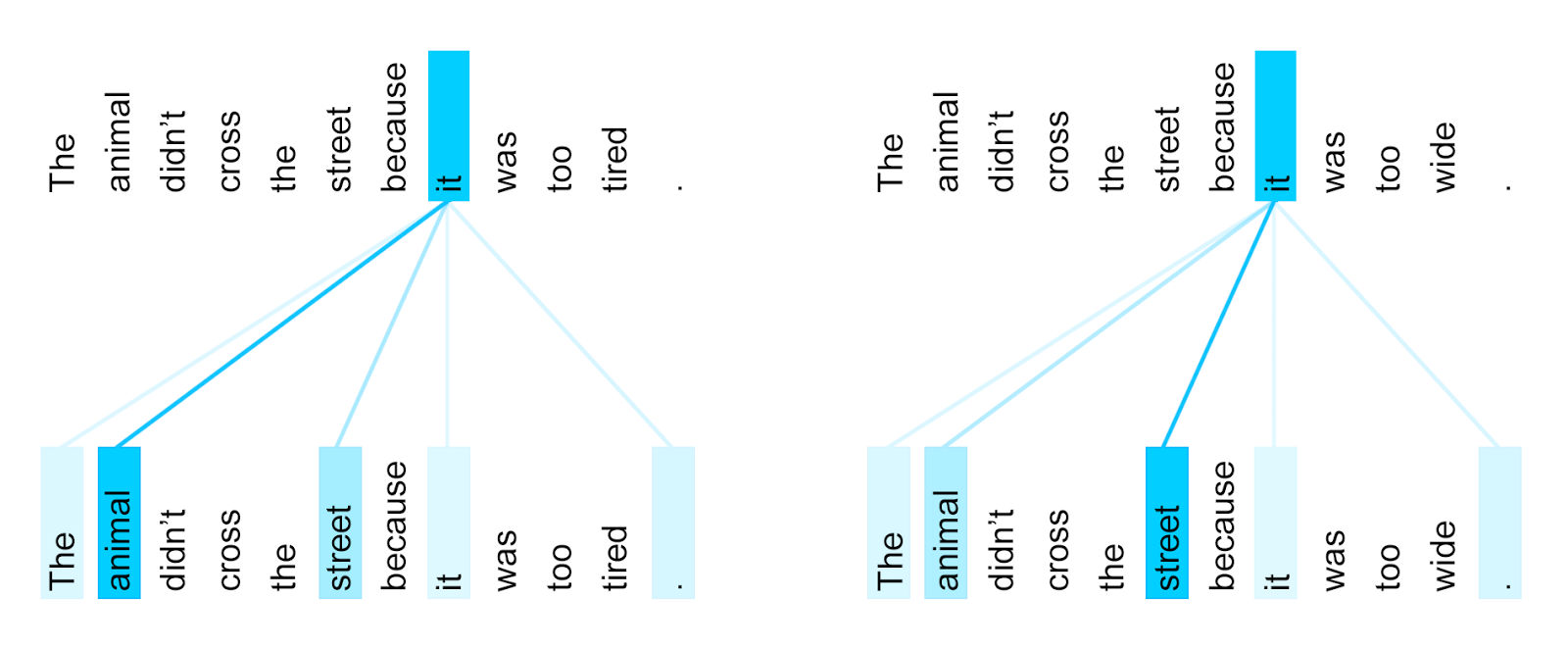

So here comes the Transformer. In the above attention work, the only attention is between the encoders and the decoder (which we call “cross-attention”), but there is no attention within the encoder itself or within the decoder itself (which we call “self-attention”). The brilliant idea in Transformer is: can we replace recurrence with self-attention? In other words, there is no “memory state” or hidden vector that compresses sequence of words; instead, each input word attends to other input words if there is a meaningful link between them, e.g., a preposition would attend to its object. This idea is inspired by the “distributional semantics” in linguistics: “a word is characterized by the company it keeps”.

Here is an illustration of self-attention from Google Researh Blog. Notice that in the first example, the pronoun “it” refers to “the animal” and it does attends to “animal” more heavily than to “street”, but in the second example, “it” refers to “the street” and it does focus more on “street” than “animal”.

In the decoder, each output word self-attends to previous output words (this differs from encoder self-attention), and cross-attends to all input words.

Here is an encoder-decoder animation from Google Researh Blog. Note that both encoder and decoder have several layers.

To summarize, RNNs use hidden state as a compressed memory, processing one word at a time, while Transformer does not compress but uses self-attention between the whole sequence of word embeddings to model sequence structure.

Just one year after the publication of Transformer, Google and OpenAI (almost simultaneously) started “pretraining” large-scale Transformer models on large amounts of text without any annotation. The goal is to recover a word given a context, which is why it is called “self-supervised learning” (briefly mentioned in Unit 3). This is a new and and very powerful paradigm which does not need annotation but greatly improves language understanding. The intuition behind it is that if I can recover any word given context very accurately, I basically understand this language really well. Similarly, for vision, you can imagine self-supervised learning as recovering a pixel given its surrounding pixels or previous pixels.

Regarding the exact word-recovery task, here Google and OpenAI diverged, and this divergence initially gave Google a huge reward financially but eventually cost it even more. Google picked the task of Cloze test, that is, to recover a word \(w_i\) by the surrounding words \(\ldots w_{i-2} w_{i-1} \square w_{i+1} w_{i+2} \ldots\). This is the same setting as the Continuous Bag of Words (CBOW) in the word embedding section but here with longer (full-sentence) context. Unlike static word embeddings where a polysemy word (like “financial bank” and “river bank”) has only one embedding, this new model, after Transformer encoding, produces “contextualized word embeddings”, so the word “bank” would have two different (final) embeddings after Transformer encoding in a sentence like “On the river bank, there is a US bank” (although the input embeddings to Transformer are still static).

This is known as the famous “BERT” model (“Bidirectional Encoder Representation from Transformers”), which is an encoder-only Transformer and thus can only be used to understand or analyze a piece text. The type of language model is known as “masked language model” because the task is to recover a masked word given context.

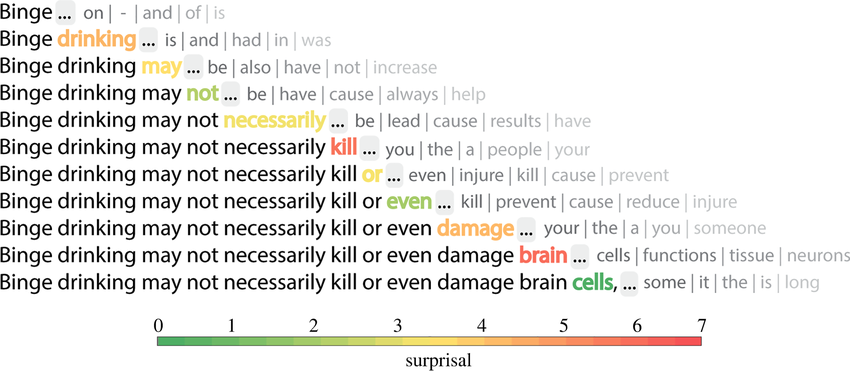

Around the same time, OpenAI thought differently. Instead of recovering a word given surrounding context, OpenAI chose to predict the next word \(w_i\) given all previous words \(w_1 w_2 \ldots w_{i-1}\). This paradigm is the classical language model setting, which is all about next word prediction and was well studied before deep learning (e.g., using \(n\)-gram models).

Unlike Google BERT which is encoder-only Transformer, OpenAI uses decoder-only Transformer (recall the original Transformer is encoder-decoder), and developed GPT (“Generative Pretrained Transformer”) models. The advantage of GPT over BERT is that because it can predict the next word given the prefix, keep doing that over and over, it can generate arbitrariliy long new text. This is why it is called “Generative AI”. By contrast, BERT can only understand text and cannot generate anything new!

But can GPT also understand language? Of course it can. This is the fundamental belief of OpenAI’s founding chief scientist Ilya Sutskever, the man behind GPT. He thought, if I can speak a language, I definitely understand it, but not vice versa! I might understand some Spanish (especially reading), but it is possible that I cannot speak it well, because producing is much harder than understanding!

It turns out that BERT is still slightly better than GPT in terms of understanding, which brought a significant improvement to Google search quality (as BERT understands search queries better than anything Google had before) and a huge financial gain. But the fact that BERT cannot generate meant that Google missed the opportunity of ChatGPT. After a few years, GPT eventually evolved into ChatGPT, the most ground-breaking App ever released in human history. This was such a big loss for Google and win for OpenAI.

Nowadays, there are numerous large language models (LLMs) and generative AI chatbots, such as Google Gemini, Deepseek, Grok, etc. These chatbots can do marvelous things such as writing poems, writing code, solving math problems, analyzing legal text, and many more. But remember, all of them are based on GPT, the decoder-only Transformer that predicts the next word.