In this section, we explore symbolic (and some hybrid symbolic + statistical) approaches to natural language processing.

Around the same time AI is being established as a field in the 1950s, the seemingly distant field of linguistics is also going through a revolution. But soon that revolution proved extremely important and relevant to the early development of both computer science and AI. That linguistic revolution is Noam Chomsky’s syntactic theory, which completely redefined linguistics as a field. Chomsky defined a hierarchy of four classes of grammar formalisms that differ in generative power (i.e., expressivity). Three out of the four grammar formalisms became cornerstones of computer science, and the most powerful one is proved to be equivalent to Turing Machine. So this “Chomsky Hierarchy” became one of the three pillars of the theory of computation, along with Turing Machine and Turing’s advisor Alonzo Church’s Lambda Calculus.

The most interesting grammar formalism in the Chomsky Hierarchy is context-free grammars (CFG), also called pharse-structure grammars, which we use to model both natural language syntax and programming language syntax. (It was independently discovered by Backus who won the Turing Award; see “Backus-Naur Form”.) A CFG consists of a set of rules, each rewriting a symbol into a sequences of other symbols. These symbols have three types:

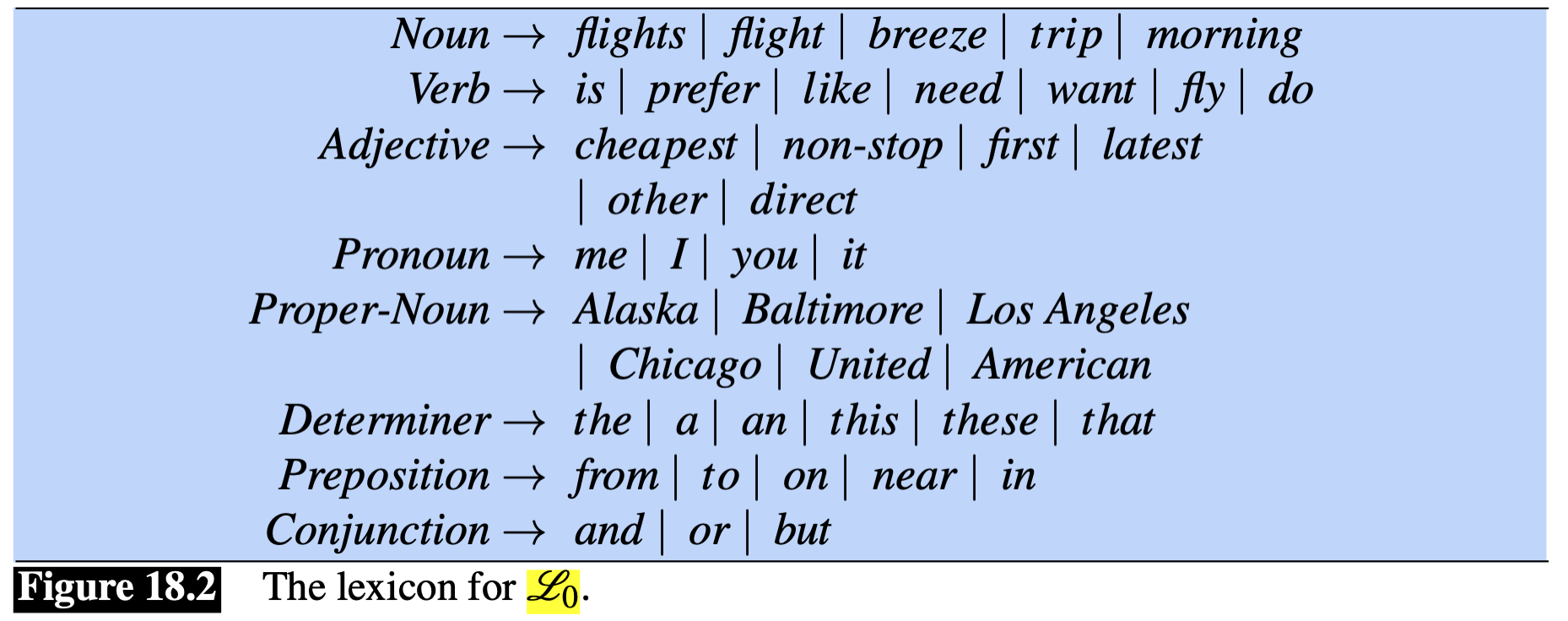

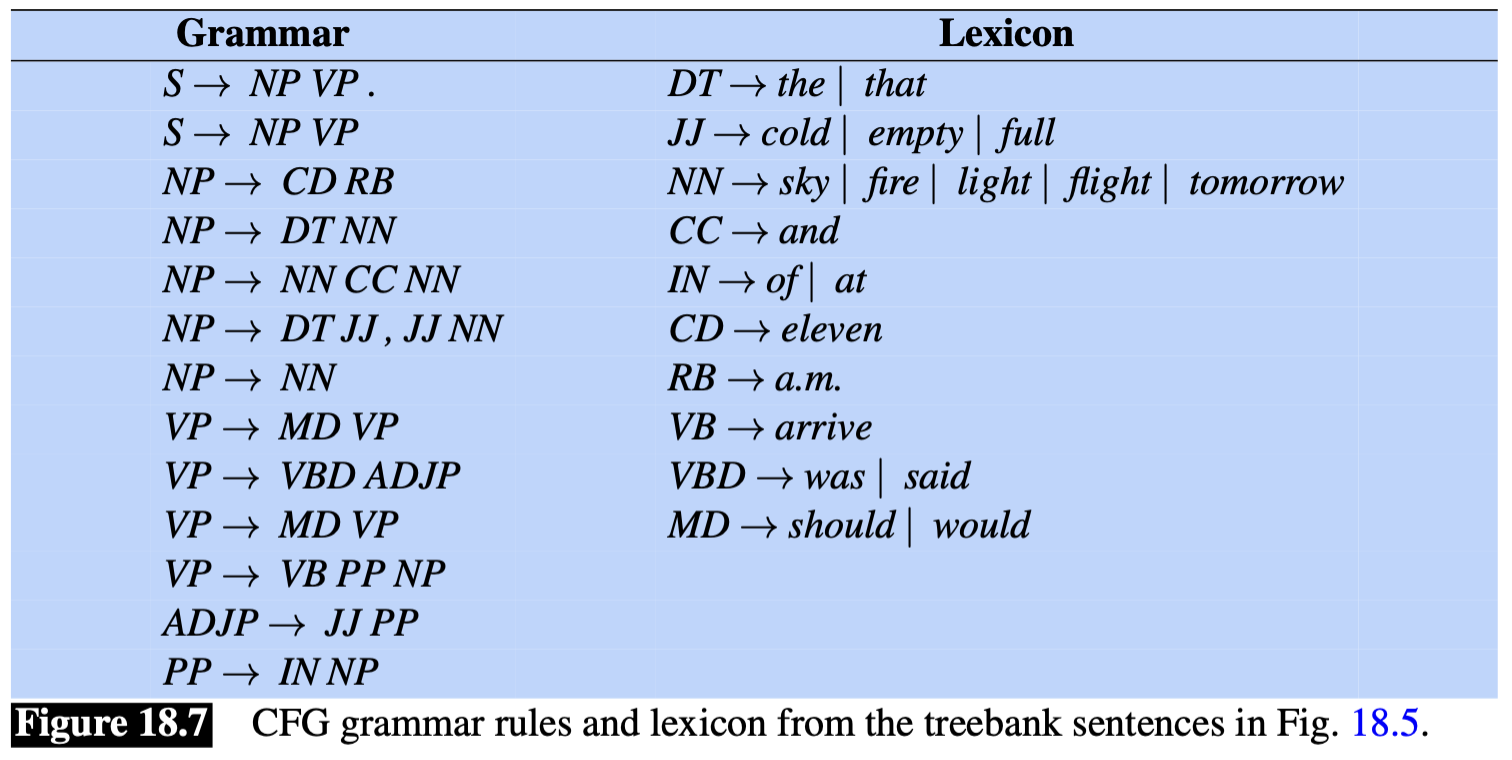

The rules from preterminals to terminals are also called “Lexicon”. Here is an example:

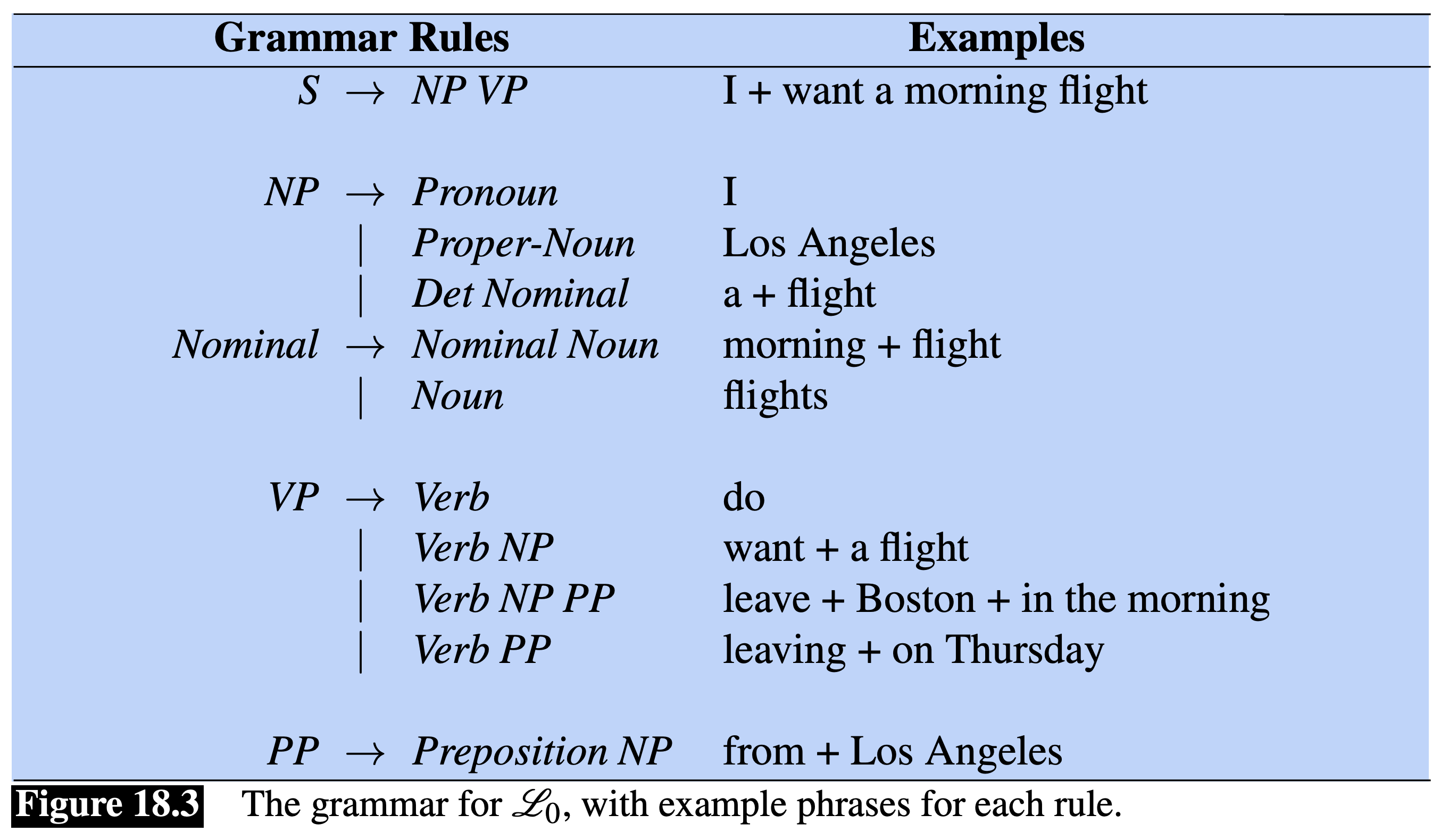

Now let’s look at the rules for expanding nonterminals, which is the core of the grammar.

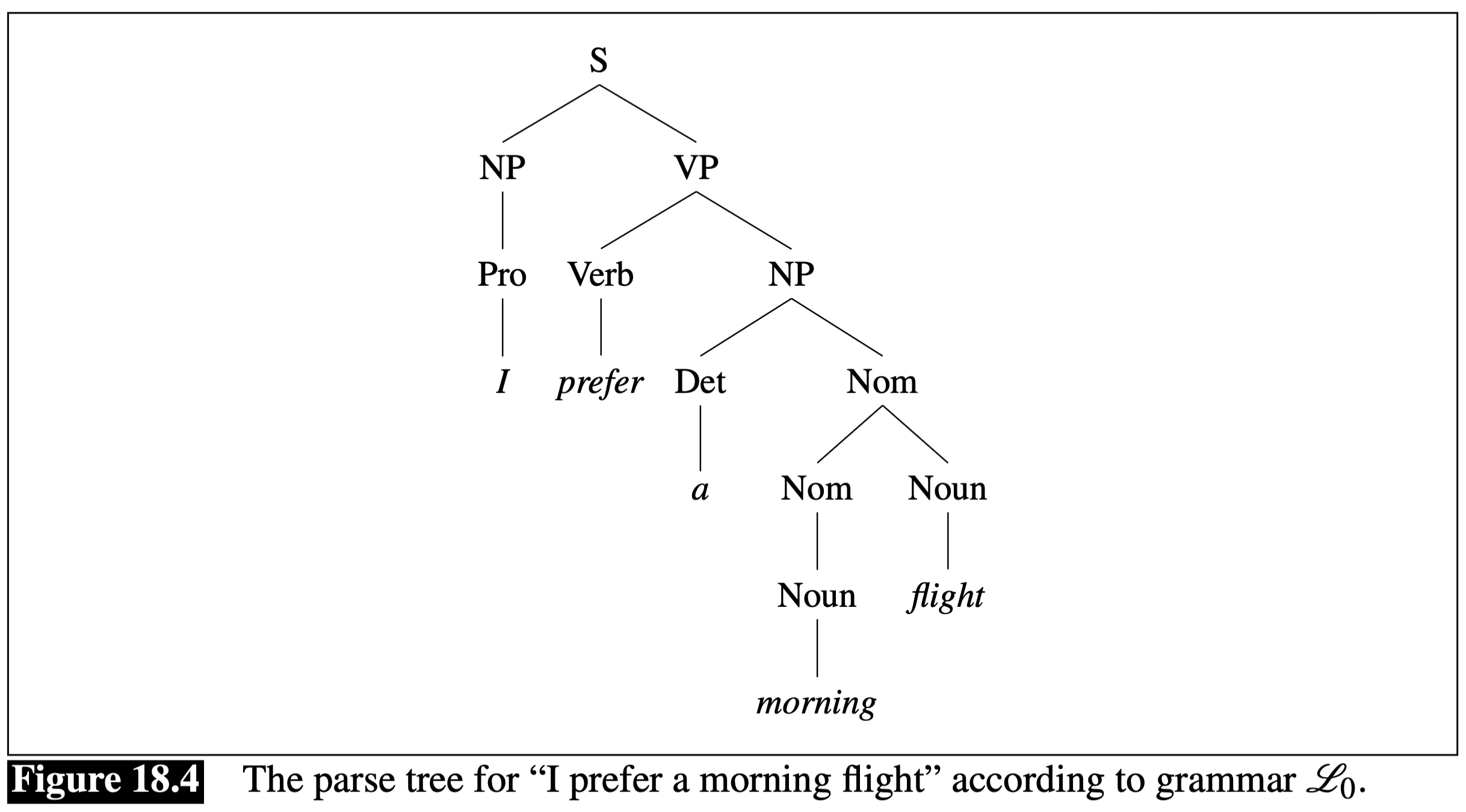

Now we can draw the syntactic structure (called “parse tree”) of a given sentence using this grammar. This is similar to the sentence diagrams you learned in English classes in your middle school and high school, but more rigorously defined. For example, the sentence “I prefer a morning flight” can be analyzed as having a noun phase (NP) as the subject and a verb phrase (VP) as the predicate, which is further decomposed into a Verb and an object NP.

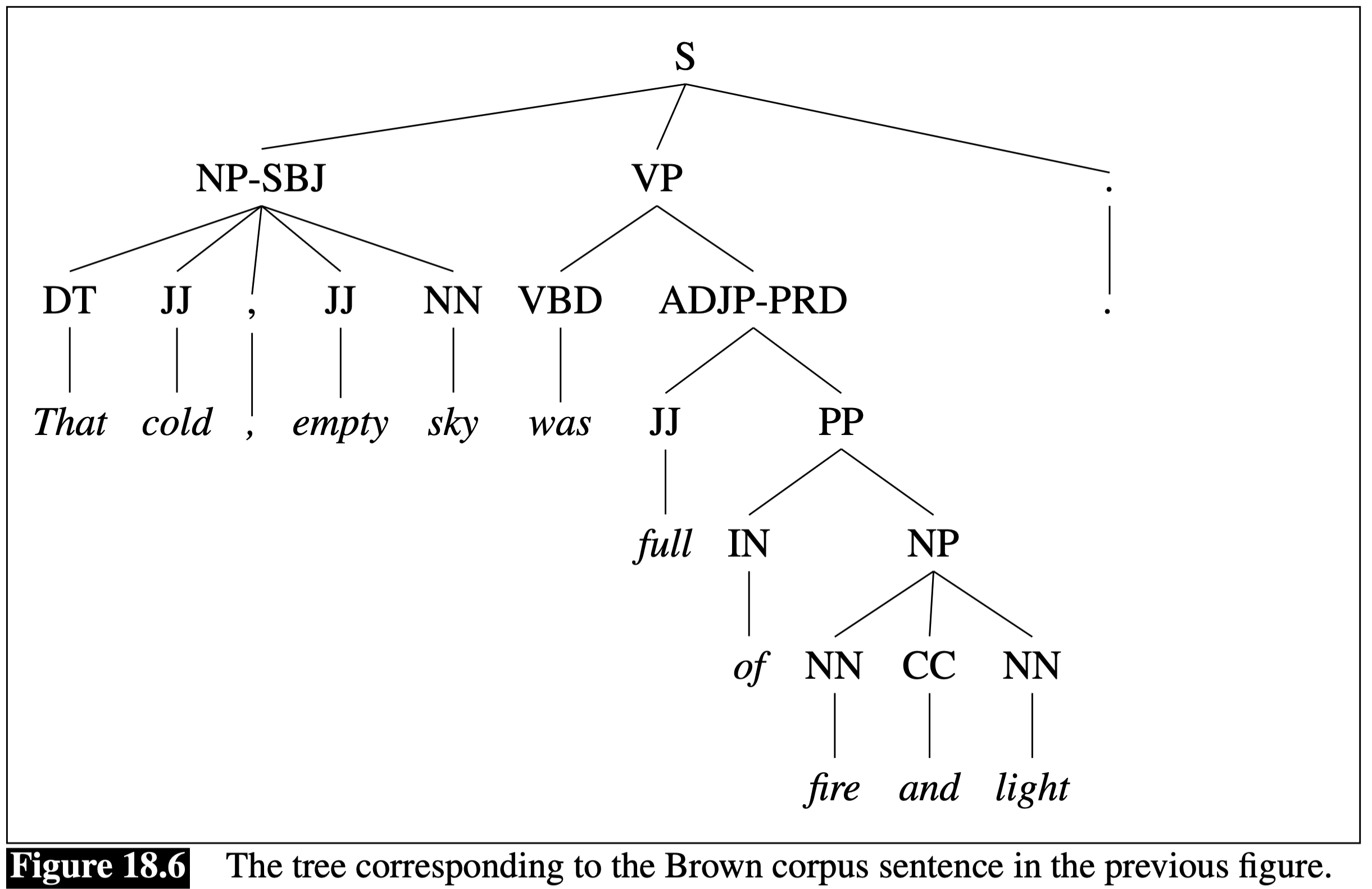

Here is a more complex parse tree with a more complex grammar.

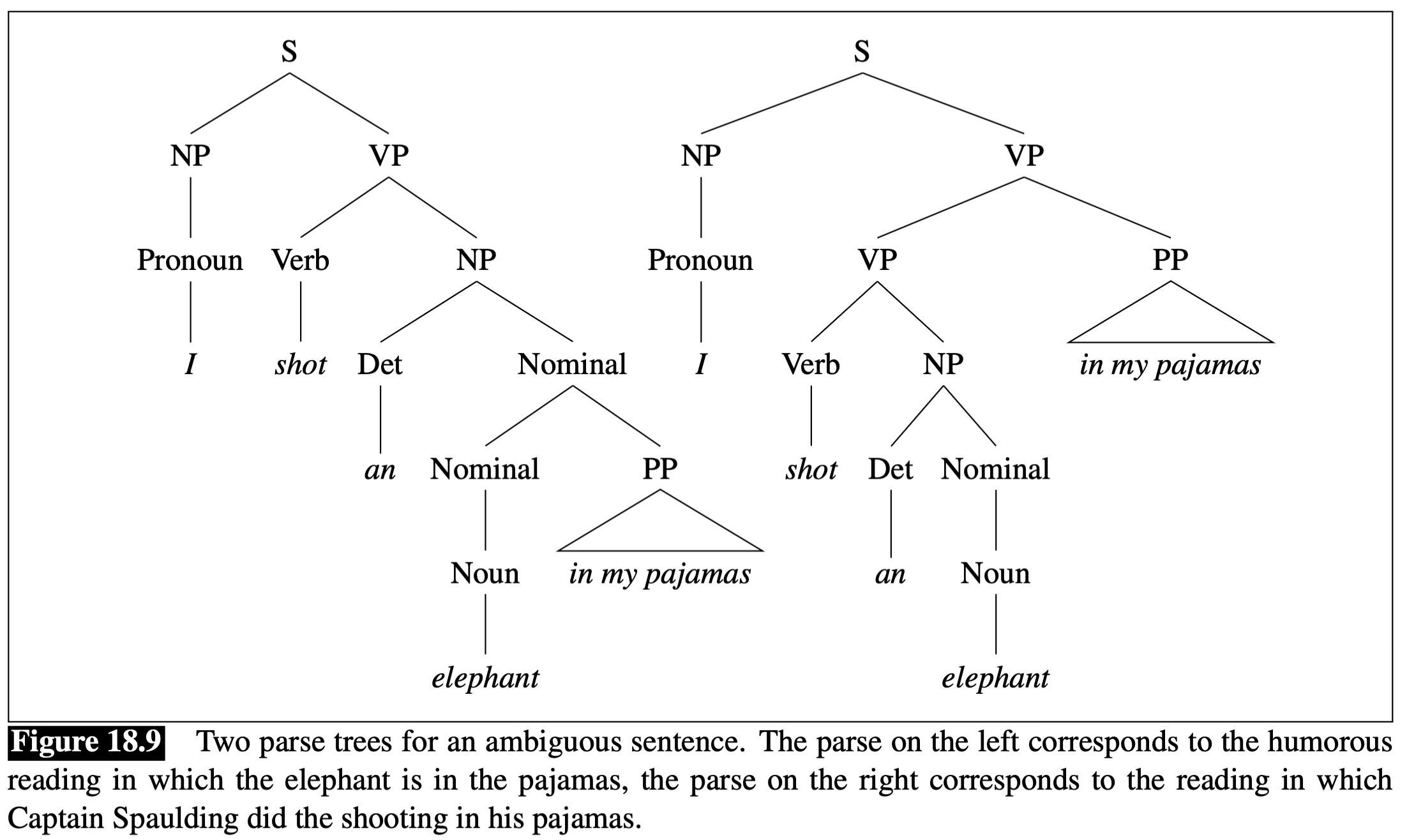

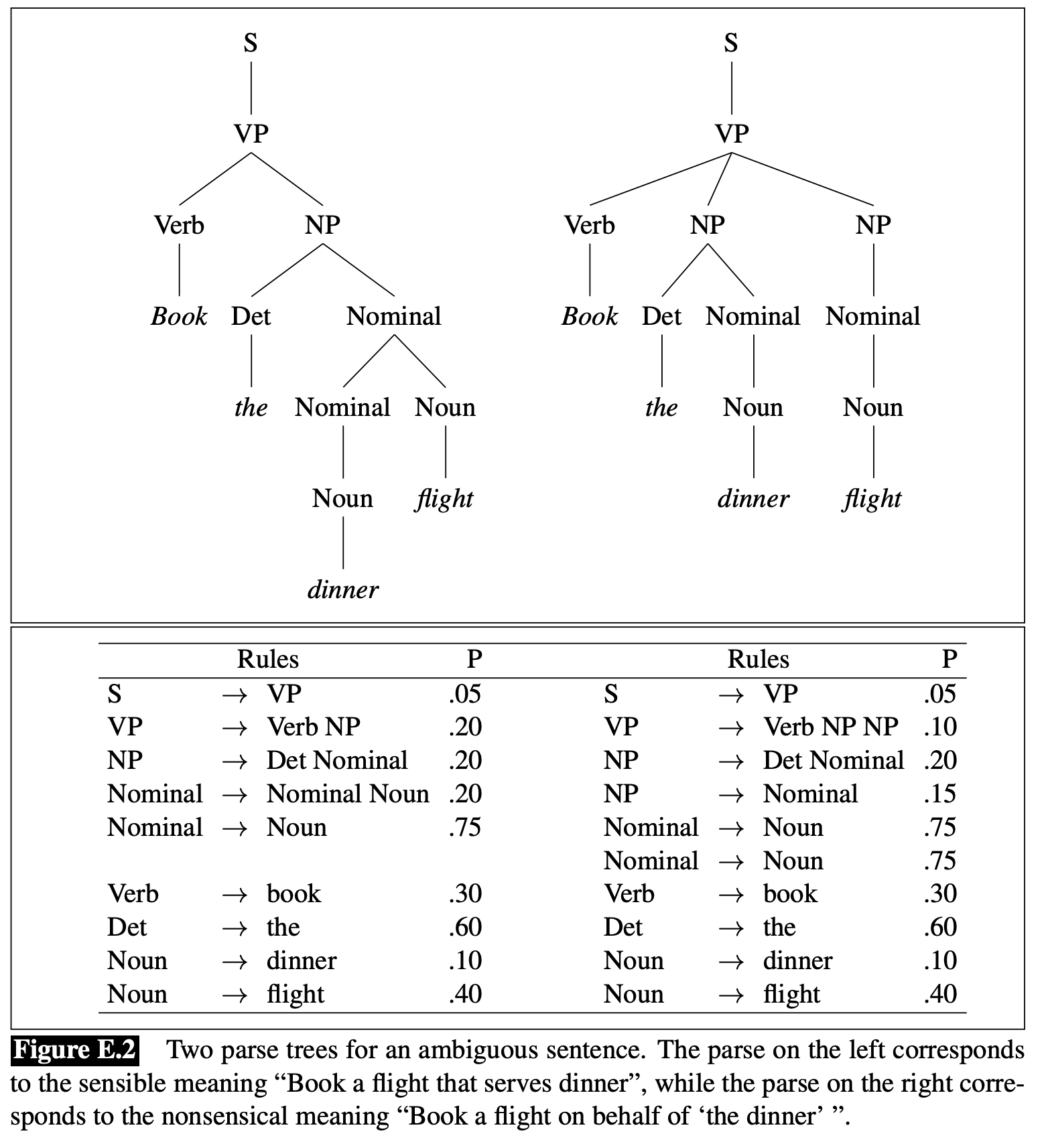

Many natural language sentences are ambiguous (such as “I saw a man with a telescope”), meaning they have two different readings. With context-free grammar, we can draw two different parse trees.

Now given a sentence and a context-free grammar, how do you automatically figure out the parse tree(s) for this sentence? This is the task of syntactic parsing, an important topic in natural language processing (which automates the sentence diagraming task you had in English classes).

The basic algorithm for syntactic parsing is called CKY (sometimes CYK), named after the three scientists (Cocke, Kasami, and Younger) who independently discovered it in the 1960s (among them, Cocke won the Turing Award for other contributions). It is based on the technique of dynamic programming (DP), which is widely used method for speeding up divide-and-conquer with tabulation to avoid repeated calculations. Actually, DP is widely used in many areas of AI, from natural language processing to speech recognition to AI search to computer vision; in fact, DP is used every minute in our modern life – your smart phone uses it to encode and decode wireless signals, your Map app (Google or Apple) uses it to find best routes, and your Google searches use it to correct spelling mistakes. So it is safe to say that DP is one of the most important inventions in human history.

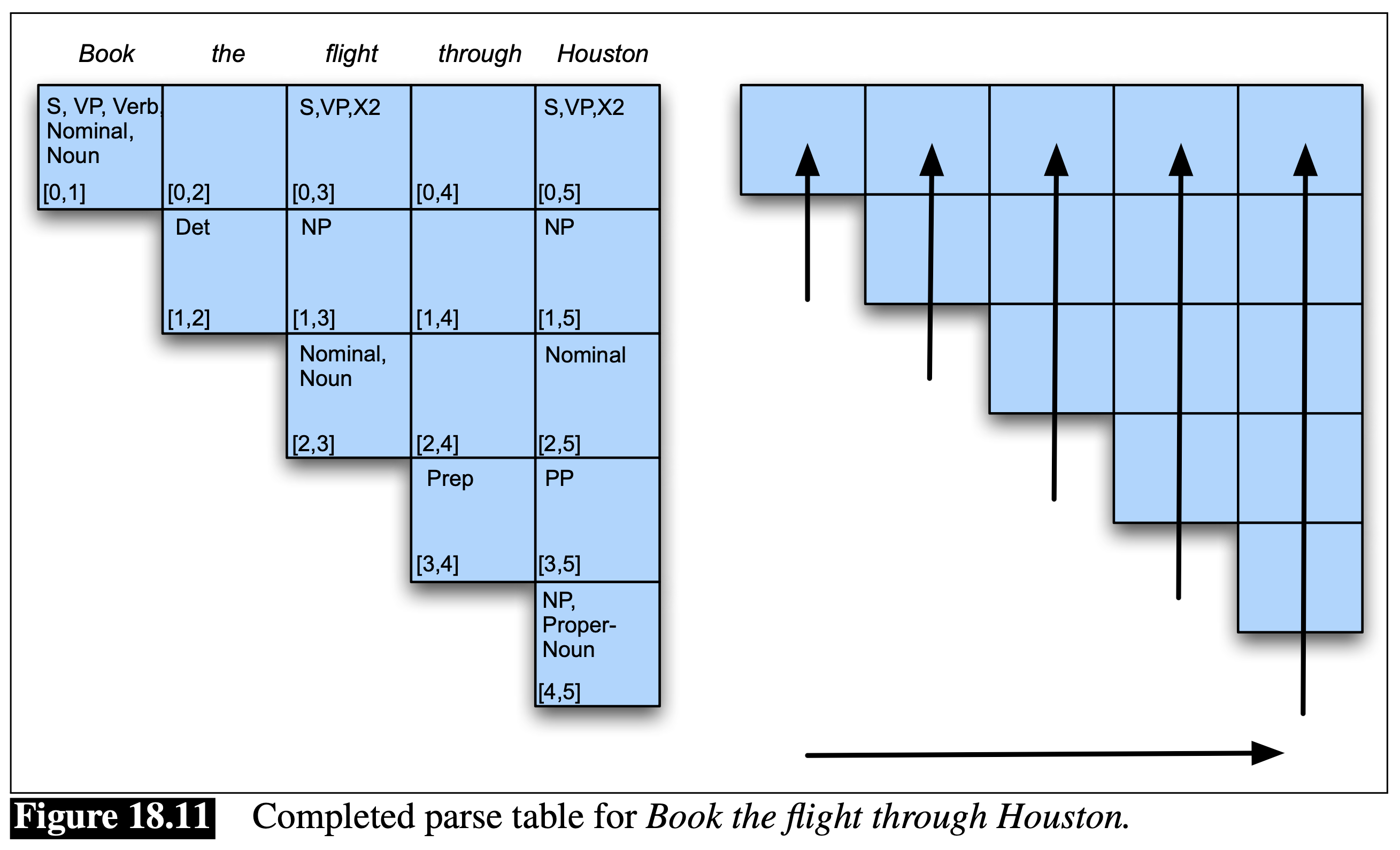

Here is the basic idea of CKY. You need to fill in a parse chart where each cell corresponds to a span (a substring) \([i,j] = w_i w_{i+1} \ldots w_{j-1}\) of the input sentence (here we use 0-based index for convenience). For example, for the input sentence “\(_0\) Book \(_1\) the \(_2\) flight \(_3\) through \(_4\) Houston \(_5\)” (with indices annotated), the span \([0,3]\) corresponds to “Book the flight”. We need to parse all spans of this sentence, although some of them make no sense such as (\([0,2]\): “Book the” and \([1,4]\): “the flight through”). We do this in an order that ensures smaller spans are done before bigger spans. In the above figure, we use the left-to-right order. First, take the first word (“Book”) and consider the span \([0,1]\) (“Book”). Next, take the second word (“the”) and consider all spans ending at it from smallest to largest, i.e., span \([1,2]\) (“the”) and then span \([0,2]\) (“Book the”). Then we take third word (“flight”) and process all spans ending at it, again from smallest to largest, i.e., span \([2,3]\) (“flight”), span \([1,3]\) (“the flight”), and span \([0,3]\) (“Book the flight”). We continue this process until we finish the last word (“Houston”) and the last span which is the whole sentence \([0,5]\) (“Book … Houston”). At the end, in the final cell \([0,5]\), we can see at least three parses (S\(_1\) S\(_2\) S\(_3\)); the first parse means (Book (the flight through Houston)) with the PP modifying the noun (flight) while the second means ((Book the flight) (through Houston)) with the PP modifying the verb (book), as the sentence is ambiguous.

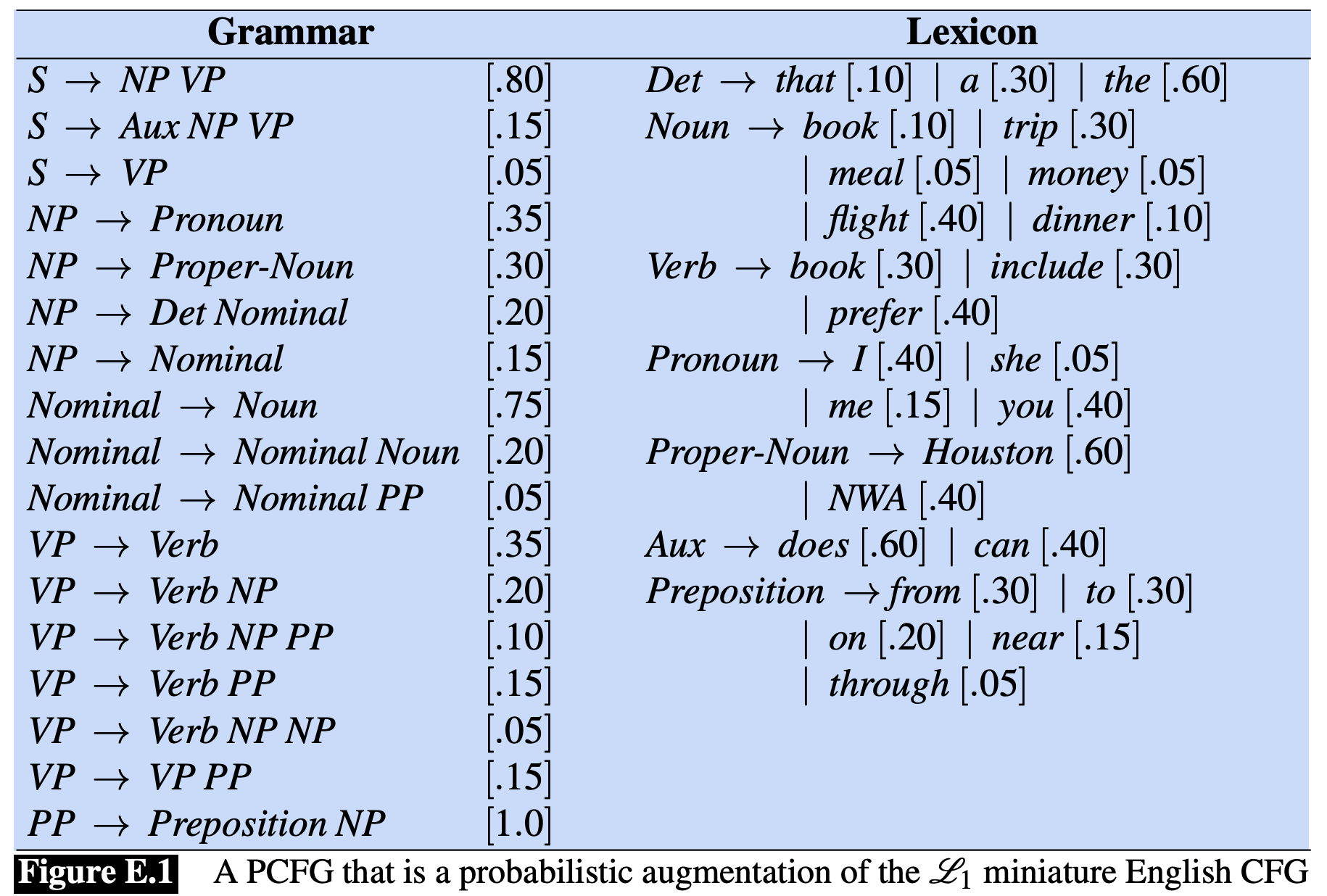

You might wonder what to do with multiple parses for ambiguous sentences. Well, this paradigm can be extended to probabilistic context-free grammars (PCFGs) and probablistic CKY parsing, so that we can figure out the most likely or most probable parse.

The above is an example PCFG. You can see that VP (verb phrase) has many rules, including:

Since ditransitives are rare, it has a much lower probability (0.05) than the other two (0.35 and 0.20); note that these probabilities are for pedagogical purposes only and do not reflect the real distribution in English. See below for how these probabilities are learned from data.

Now we can use this PCFG and redo CKY for an ambiguous sentence “Book the dinner flight”. The second reading “(Book (the dinner) (flight))” is nonsensical, as if we book a flight for “the dinner” (ditransitive, “flight” is the direct object), so it has a smaller probability.

We should note that the probabilities associated with these rules are learned by statistical and/or machine learning techniques from data. Linguists have constructed large-scale annotated datasets called “treebanks” where each sentence is annotated with a parse tree according to a context-free grammar. By looking at all these parse trees, we can count how many times a VP occurs, and how many times a VP is rewritten into VP PP. So the probability of this rule is simply:

\[ p(\text{VP} \rightarrow \text{VP}\; \text{PP}) = \frac{\#(\text{VP} \rightarrow \text{VP}\; \text{PP})} {\#(\text{VP})} \]

Let’s say we have 1000 VP’s and 200 of them are rewritten into VP PP, then this rule has probability 0.2. Note that the probabilities of all VP rules sum up to 1 (i.e., normalized).

Since the probabilities are learned from data, this part is not purely symbolic, but a hybrid between symbolic and data-driven AI. This hybrid approach became the dominant method of natural language processing in the mid-1990s when the famous Penn Treebank is released. It became overshadowed by the deep learning approaches in the mid-2010s.

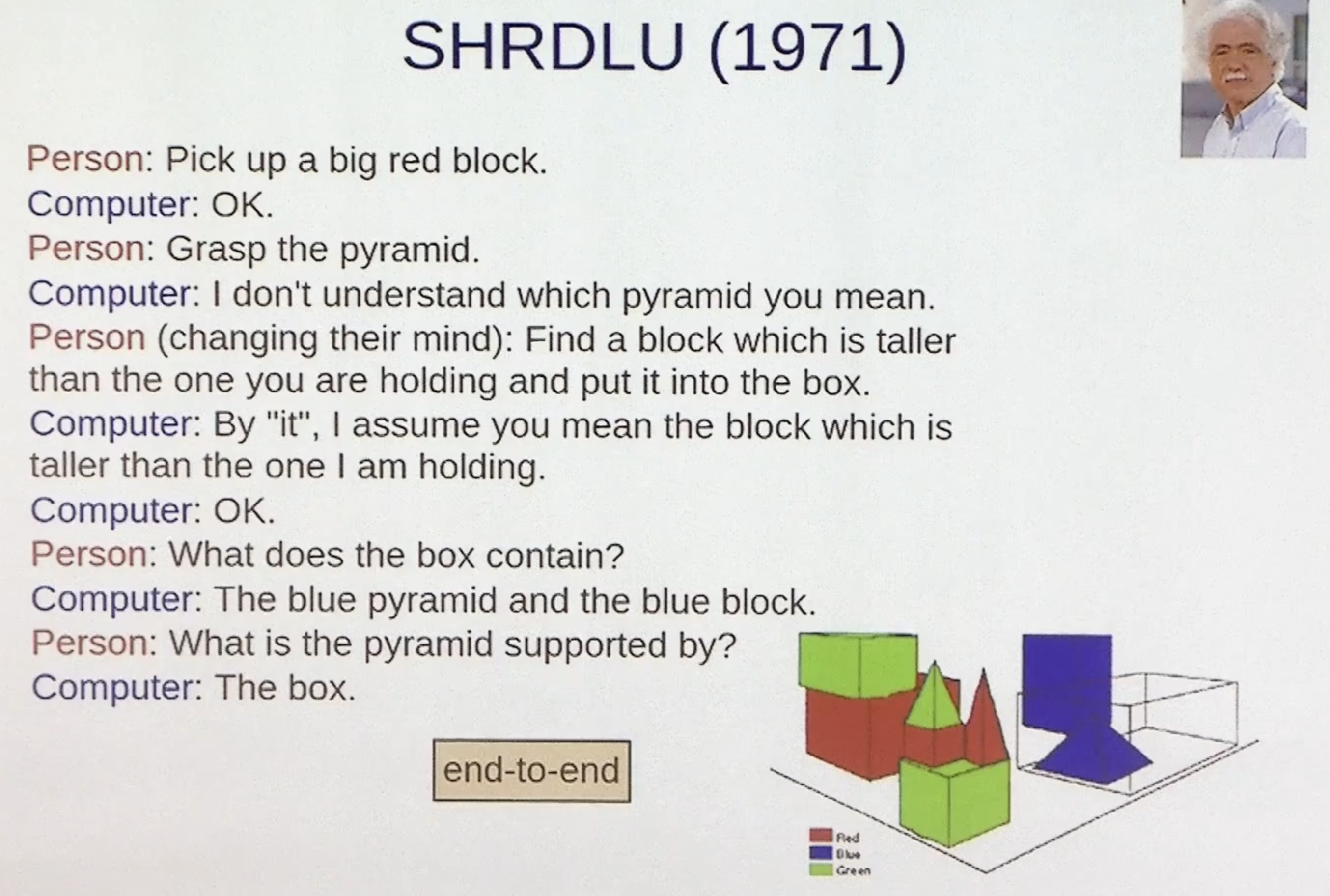

Partially based on grammars and parsing, AI researchers built some very impressive early chatbots in the 1960s. The two most notable ones are ELIZA and SHRDLU. Although they were certainly very limited compared to today’s chatbots such as ChatGPT, it is surprising that in some aspects, some people still think they are smarter than ChatGPT.

ELIZA was developed at MIT by Joseph Weizenbaum from 1964 to 1967. It uses a relatively simple form of parsing based on pattern matching and substitution of keywords. These pattern-matching rules are organized in separate “scripts”, and the most famous one is DOCTOR which simulates a psychotherapist that often reflects back the patient’s words to the patient.

You can still try ELIZA here.

SHRDLU was developed at MIT by Terry Winograd in 1968-1971 as his PhD thesis. It is not just a chatbot, but rather an interactive environment to explore a 3D “blocks world”, where the user can give commands like “Pick up the red block” and the computer can ask for clarification like “which one?”. The user then clarifies “the one on top of the blue cube”, and the computer picks up the right block. SHRDLU was much more sophisticated than ELIZA and used a comprehensive syntactic and semantic parser as part of an integrated system. Because SHRDLU interacts with a 3D world, it is beyond modern text-based chatbos like ChatGPT in that sense, and is more towards the “World Models” direction in the future of AI; see Unit 5.

Here is a very good teaching video from Prof. Jordan Boyd-Graber of University of Maryland on early question answering which includes SHRDLU:

Videos