\(\renewcommand{\vec}[1]{\mathbf{#1}}\)

\(\newcommand{\vecw}{\vec{w}}\) \(\newcommand{\vecx}{\vec{x}}\) \(\newcommand{\vecu}{\vec{u}}\) \(\newcommand{\veca}{\vec{a}}\) \(\newcommand{\vecb}{\vec{b}}\)

\(\newcommand{\vecwi}{\vecw^{(i)}}\) \(\newcommand{\vecwip}{\vecw^{(i+1)}}\) \(\newcommand{\vecwim}{\vecw^{(i-1)}}\) \(\newcommand{\norm}[1]{\lVert #1 \rVert}\) \(\newcommand{\fhat}{\hat{f}}\)

Exploration 3.2: Different Settings of Machine Learning

There are many different types of learning settings:

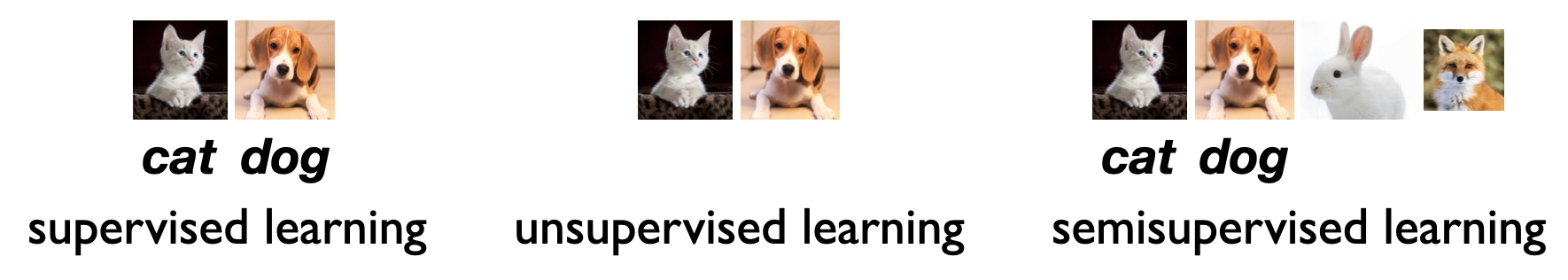

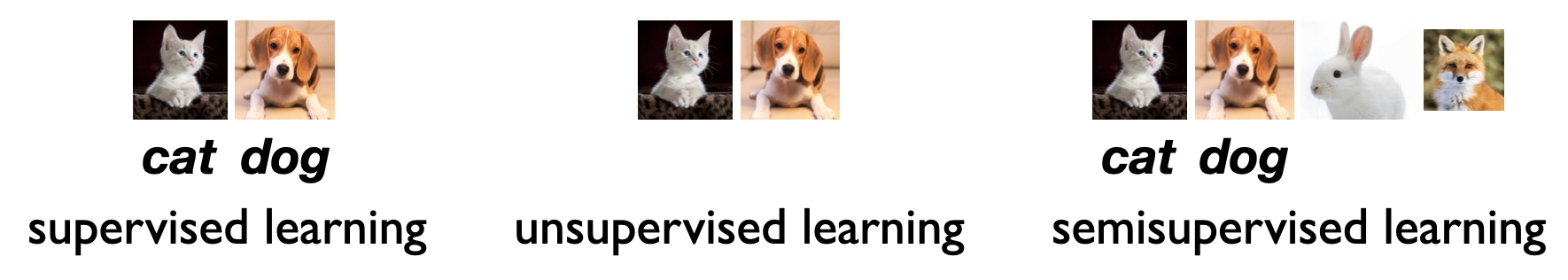

supervised learning: training data is a collection of labeled training examples, where each example is annotated with a desired output (i.e., label). For example, in hand-written digit classification, the training data might contain 10,000 images, each with a label in \(\{0,1,2,\ldots,9\}\). In housing price prediction, our training data might be 10,000 houses, each with features such as square footage and lot size along with its market price. The model is trained to predict the desired output for an input example. Scenarios: classification and regression. This unit is mostly about supervised learning.

unsupervised learning: training data is unannotated and thus does not include the labels. In the hand-written digit classification example, the training data is just a set of images. Here we aim to find the inherent structures within the data. Scenarios: clustering and dimensionality reduction.

semi-supervised learning: Part of the training data includes labels, while part of it does not. Often the unlabeled part is much bigger because annotation is expensive. For example, we might have 10,000 images with labels, plus 100,000 images without labels. We use the unlabeled part as a supplement to improve the model trained on the labeled data.

partially observed learning: Each training example (input) comes with a label (output), and how to get from the input to the output is not annotated. For example: in machine translation (let’s say from English to Chinese), the input data contains one million (English, Chinese) sentence pairs, but the correspondence between English and Chinese words (called “word alignment”) is not annotated.

self-supervised learning: the training data is unlabeled, such as pure text or image, but we predict part of it given the rest. For example, we can train a language model to predict the next word given previous words; we can predict a pixel given the other pixels in an image. This technique has given rise to powerful applications such as ChatGPT.

reinforcement learning: the training data (in this case, the optimal sequence of actions to perform a task) is not labeled, but you can get rewards from the environment. Think about playing chess: there is no annotation to tell you whether each move is good or bad, but at the end of each game, you get a reward signal of win (+1), lose (-1), or draw (0). The goal is to learn from these (often delayed) reward signals and attribute them to individual actions, so that good actions (which eventually lead to positive rewards) will be preferred.

In supervised learning, the training examples are labeled, and there is some unknown function that generates the data (with labels). The job of machine learning is to recover this hidden function from the labeled data, or to find a good approximation of it. This approximate function is known as the prediction rule learned from data.

We differentiate two types of function which correspond to two subsettings of supervised learning, classification and regression:

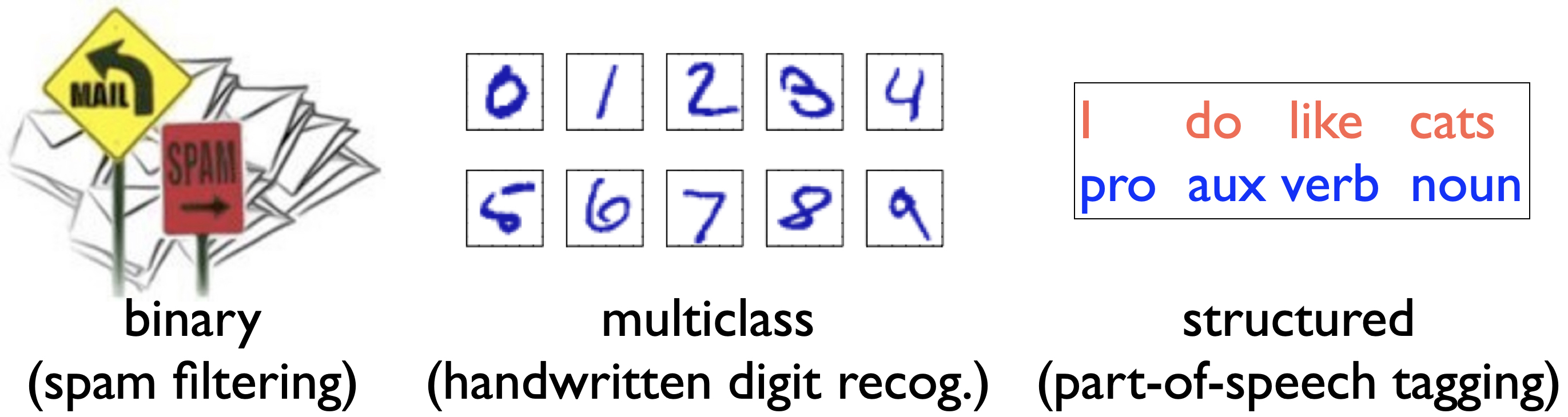

The output (i.e., label) is discrete, e.g., each \(\{+1,-1\}\) or \(\{0, 1, 2, \ldots, 9\}\). This is known as classification, which is the most widely used setting in machine learning. There are three subtypes of classification:

binary classification: the output is binary, e.g., \(\{+1,-1\}\) for spam detection (spam, not spam) or sentiment classification (positive, negative).

multiclass classification: the output is multiclass, e.g., \(\{0, 1, 2, \ldots, 9\}\) for handwritten digit classification, or \(\{-1,0,+1\}\) for three-way sentiment classification (negative, neutral, positive).

structured classification: the output is a structured object such as a sequence (e.g., part-of-speech tags, one for each word in the input sentence) or tree (e.g., syntactic parse tree for the input sentence). This setting is more involved than the previous two settings in that the size of possible output labels grows exponentially with the size of the input sequence. Due to its advanced nature, this topic is beyond the scope of this course, but is very useful in two fields: natural language processing (computational linguistics) and computational biology.

Supervised learning is particularly useful in the following scenarios:

When there is no human expert

e.g., protein folding, predicting properties of a new molecule

When humans can perform the task but can’t describe or explain it

e.g., face recognition, optical character recognition (OCR), speech recognition

When the desired function changes frequently

e.g., housing price prediction, stock price prediction, spam filtering

When each user needs a customized function

e.g., speech recognition, speech synthesis, spam filtering