\(\renewcommand{\vec}[1]{\mathbf{#1}}\)

\(\newcommand{\vecv}{\vec{v}}\) \(\newcommand{\vectheta}{\pmb{\theta}}\)

Exploration 4.3: Deep Learning for Language (Part 1): Word Embeddings

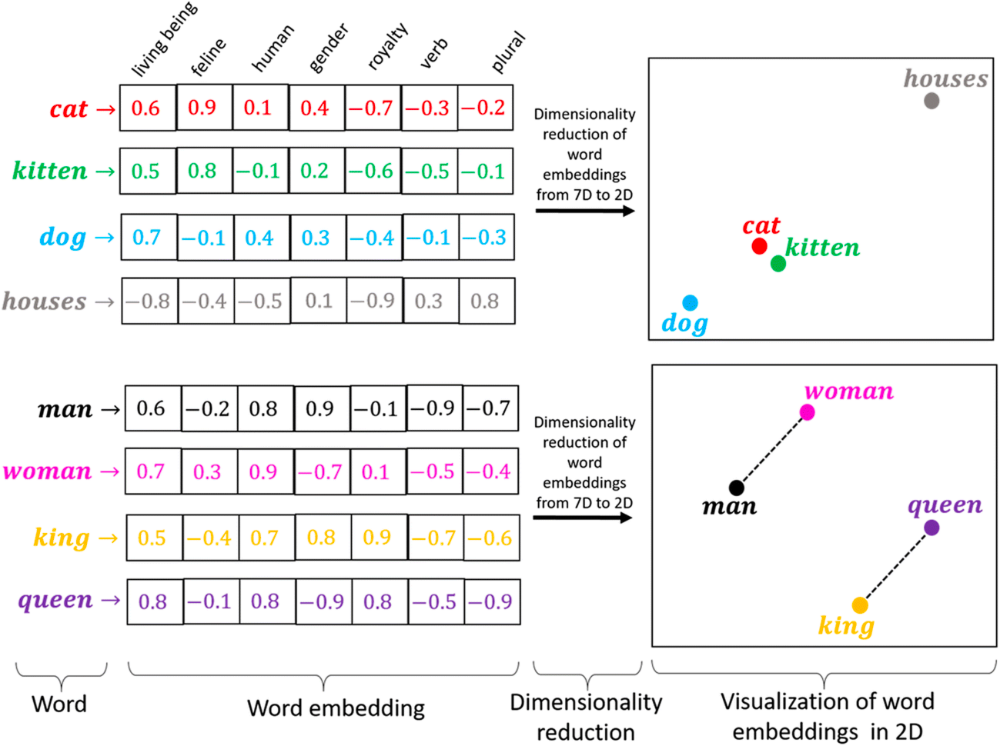

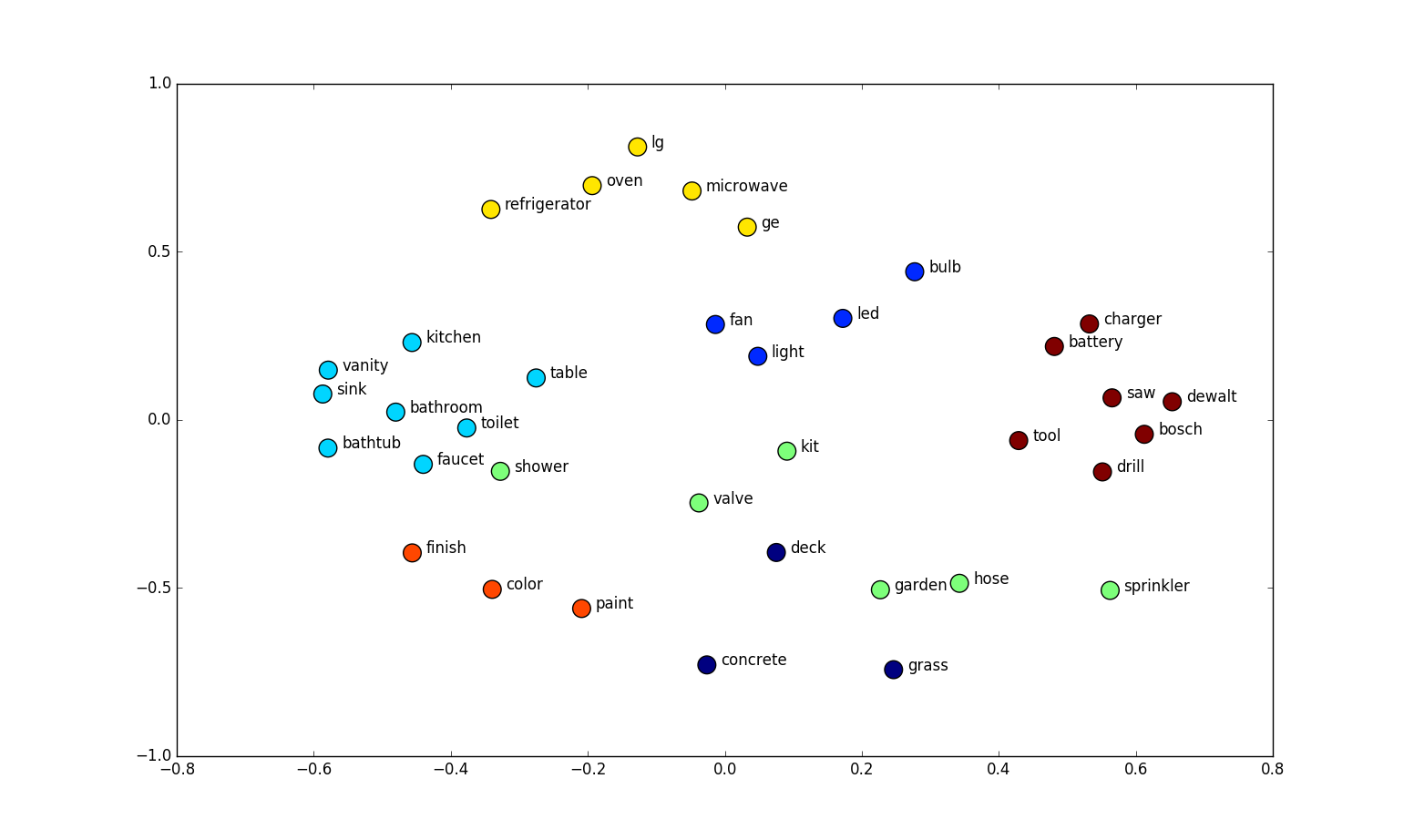

In the previous exploration, we discussed how to apply deep learning to vision. But in order to apply it to natural language, we face a bigger challenge. You see, unlike vision, our language is inherently discrete (words) and symbolic, but deep learning is fundamentally connectionist, continuous, and anti-symbolic. So how to unify them? Well, we first need continuous representations of discrete words, so that deep learning can take them as inputs. In other words, we want to view words like “cat” and “bunny” as vectors in some high-dimensional space, and similar words would have similar vectors. This is known as “word embeddings”, a fundamental topic in deep learning-based NLP. Today’s generative AI such as ChatGPT is all based on this very concept.

Word embeddings are continuous vector representations of words that capture semantic and syntactic relationships between words. In this exploration, we will cover the basics of word embeddings, their properties, and how they can be trained.

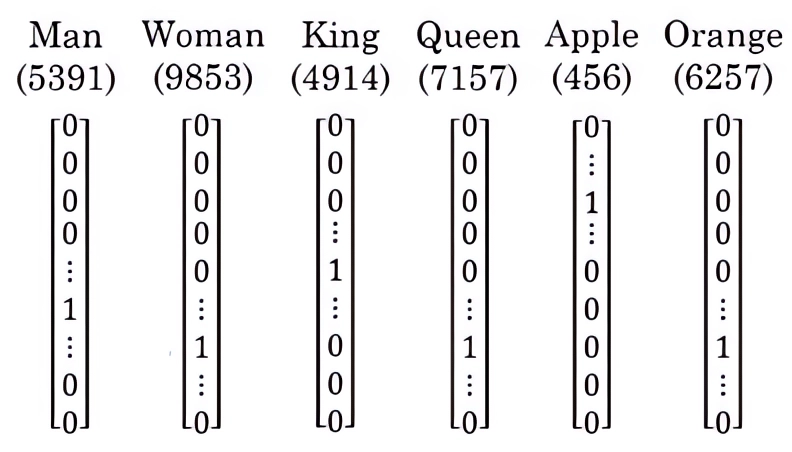

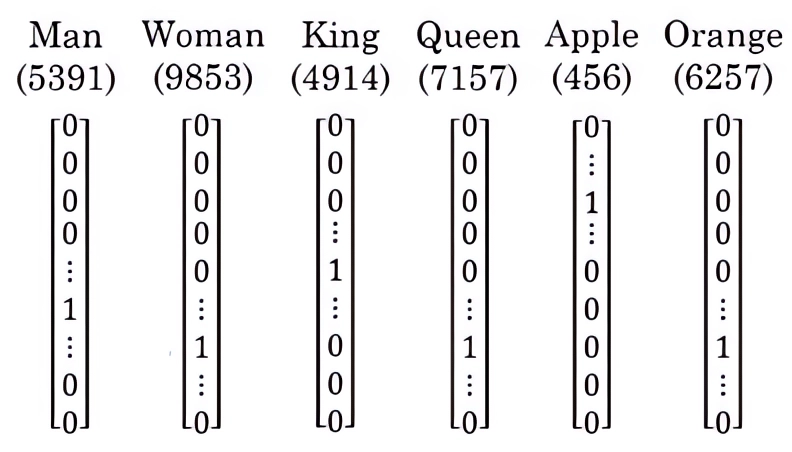

Traditionally, in machine learning and NLP, words were represented

using one-hot vectors, where each word in the vocabulary is assigned a

unique index (e.g., in the following example, “Orange” is assigned the

index of 6257) and is represented as a binary vector with a single

1 in the position corresponding to the word’s index and

0s elsewhere. To convert a word to its one-hot vector

representation, a look-up process is employed: first, the word’s index

is determined from the predefined vocabulary, and then a vector of the

same length as the vocabulary is created, with the element at the word’s

index set to 1, and all other elements set to

0.

However, one-hot representations are sparse and do not capture any semantic information about the words. To address this limitation, continuous representations such as word embeddings are used. These dense vector representations are capable of capturing semantic and syntactic relationships between words, making them more suitable for NLP tasks.

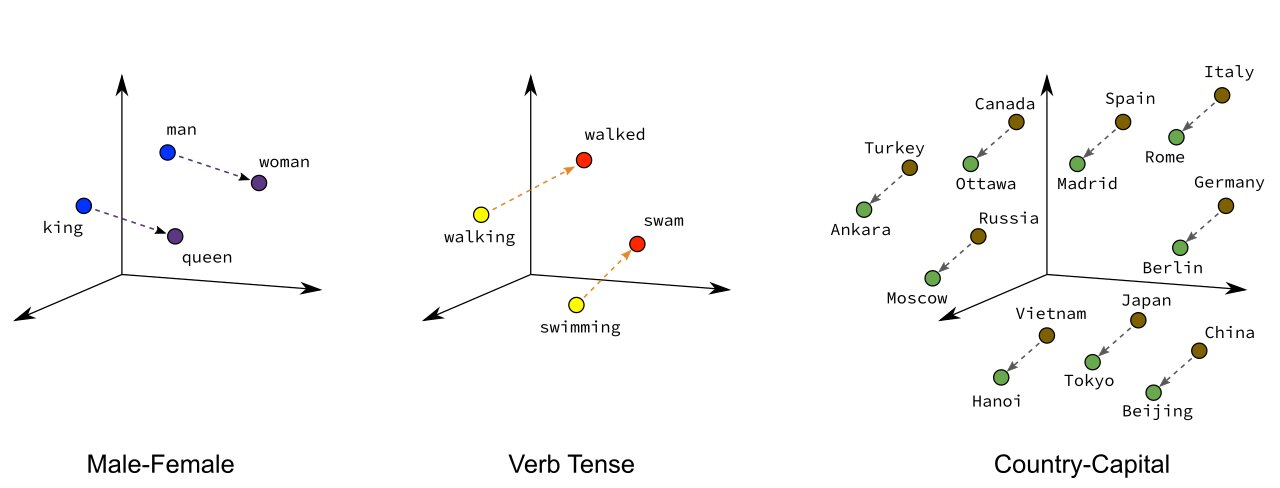

Some interesting properties of word embeddings include:

Analogies: Word embeddings can capture analogies, such as “man - woman = king - queen”. This can be illustrated by performing vector arithmetic on the embeddings and finding the closest word in the vector space. For example:

\[\text{embedding}(\text{"man"}) - \text{embedding}(\text{"woman"}) + \text{embedding}(\text{"queen"}) \approx \text{embedding}(\text{"king"})\]

There are several models and algorithms for learning word embeddings, including:

Word2Vec: This is the most famous family of models that learn word embeddings using a shallow neural network. Word2Vec is trained to predict a word given its context or the context given a word:

GloVe (Global Vectors for Word Representation): A model that learns word embeddings by factorizing a word co-occurrence matrix. The main idea behind GloVe is that the relationships between words can be encoded in the ratio of their co-occurrence probabilities. GloVe is trained to minimize the difference between the dot product of word vectors and the logarithm of their co-occurrence probabilities. By doing so, it learns dense vector representations that capture semantic and syntactic information about words.

FastText: An extension of the Word2Vec model that represents words as the sum of their character n-grams. FastText can learn embeddings for out-of-vocabulary words and is more robust to spelling mistakes. FastText can be trained using either the Skip-gram or CBOW architecture, similar to Word2Vec.

To train word embeddings, a large text corpus is required. The text corpus is preprocessed (e.g., tokenization, lowercasing) and fed into the chosen model. The model learns the embeddings by updating its weights using gradient-based optimization algorithms (e.g., stochastic gradient descent).

In many cases, it is not necessary to train word embeddings from scratch. There are several pre-trained word embeddings available that can be used directly in NLP tasks or fine-tuned for specific domains. Some popular pre-trained word embeddings include:

Google’s Word2Vec: Pre-trained on the Google News dataset, containing 100 billion words and resulting in a 300-dimensional vector for 3 million words and phrases.

Stanford’s GloVe: Pre-trained on the Common Crawl dataset, containing 840 billion words and resulting in 300-dimensional vectors for 2.2 million words.

Facebook’s FastText: Pre-trained on Wikipedia, containing 16 billion words and resulting in 300-dimensional vectors for 1 million words.

I have added more details on the properties of word embeddings, including some examples, and explained how to use pretrained embeddings in NLP tasks in the word_embeddings.html file below:

Pretrained word embeddings can be used as a starting point for various NLP tasks, such as text classification, sentiment analysis, and machine translation. They can be used in the following ways:

As input features: The word embeddings can be used as input features for machine learning models, such as neural networks or support vector machines. For example, in a text classification task, you could average the embeddings of all words in a document to obtain a document-level embedding, which can then be used as input to a classifier.

As initialization for fine-tuning: In some cases, it might be beneficial to fine-tune the pretrained embeddings on a specific task or domain. You can initialize the embedding layer of a neural network with the pretrained embeddings and then update the embeddings during training. This can help the model to better capture domain-specific knowledge.

In combination with other embeddings: Pretrained embeddings can be combined with other types of embeddings, such as character-level embeddings or part-of-speech embeddings, to create richer representations for NLP tasks.

By using pretrained embeddings, you can leverage the knowledge captured from large-scale text corpora and improve the performance of your NLP models.

Videos